Spring

April 15, 2015 § 26 Comments

“Unlatch the door to the canary’s cage, indeed, rip the little door from its jamb.” – Billy Collins

The evening is soft now. Dinner is over and I have come out to the back step to watch the bay and witness the arrival of spring. Mid-April is decidedly confident, like a starlet with an abundance of dogwood and cherry blossoms, and oh, those azaleas and the way the wisteria is already snaking through the trees. It would be so easy to stay right here and watch the day end. I don’t want to put anyone to bed or sweep the crumbs from the floor or wash the pan. Then the mocking bird flies out of last year’s tomato plants, its striped wings as sharp as its message is clear. I should go back inside. I should finish the chores. But inside, I hear the boys laughing, not bickering yet, so I sit a bit longer with my palms turned up, feeling spring in my hands until the cry of a jay makes me wince. He is so loud and insistent he competes with the artillery on the other side of the water, and I try to remember we have to let all the birdsong in if we are going to hear any of it.

This morning I walked with a friend, and we passed a group of Marines practicing some kind of martial arts, one kneeling behind the other within a border of sand bags, an elbow in camouflage hugging a neck. They were gentle in their demonstration of this fierce art, and I felt the effect this particular way they train has on my heart. They are careful even as they are practicing the quick skill of killing.

Somehow, overnight, a dogwood tree has turned white in my neighbor’s back yard, right in front of the water, the bay that is now calm and waveless, the whitecaps somehow turning into blossoms in front of my eyes. And this is why spring is so painful to me: all this unfurling and opening. All this softness and ease. Here, the sun says, fooling you. Just sit with me and I’ll be gentle and easy on your skin.

The other day I was sitting outside of the elementary school, waiting for Oliver to come out and wave his lunch box at me. He hates the bus and he says it’s too loud for him to read his book on the way home. We are so alike we don’t always get along, but this I can understand. As I sat on the concrete waiting, I saw a Marine who came to the yoga classes I used to teach and we waved to each other, but in that awkward way. As Henry got closer, he questioned me about my shoulder.

“Are you doing yoga again ma’am?” Henry asked and I told him I’m getting back into it and what about him? Another Marine passed with his two daughters, both of the girls in hot pink, which would make you blink: that contrast between a shaved head and a princess gown, the unlikeliness of softness against the scratch of this world.

Suddenly I miss teaching so much it hurts the way all of this unfolding hurts. The way unfurling yourself to the sun feels, the way your skin peeled off after that bike ride you took on the 101 twenty years ago and the way he put his palm on the back of your burned shoulder blade, right at the place where your heart meets your spine. “Can I help?” you asked then as you stood in his kitchen, watching him spin avocados into guacamole. He smiled at you. “Just charm me,” he had said, while that smile crept in like a criminal.

I told Henry to check out the free classes on YouTube. “Search for ‘Power Yoga’,” I told him. “You’ll find good stuff there.”

“Aw,” he said, “There’s no one like you.” But I know he is charming me because he keeps on walking, his head down and a smile sneaking into his cheeks. Heart and backbone, each holding each other up even as they are completely incompatible. Spring is so misguided, thinking it’s safe to come out, believing it’s acceptable to live for only a moment, that the month of April could ever be enough. I wonder if there is a difference between the Marines with elbows in choke holds and the ones in the yoga classes I used to teach, their shoulders and spines beginning to soften into a twist. And I think there is no difference in gentleness, no matter what pose, the way they all seem to circle around when it’s over and light cigarettes as if they were incense.

Autumn and winter are so comfortable, all clove and wool, mitten and fireplace. I am not sure I can handle this though: the smell of cooked meat wafting through the screen door, which isn’t who I thought I would be. I thought I would be sprouts and hummus, veggie burgers and broccoli, but since Scott has gone we have tacos on Monday nights, after a free yoga class for the teachers while the boys build Legos in the back of the classroom. All these opposites colliding like the osprey who flew overhead last night, clutching the fish in its talons. “You can’t be vegetarian when your husband is deployed,” my neighbor told me while the sun beat down last June. “It’s just too tiring.” And I am disappointed in myself that this has turned out to be correct. I am disappointed I am not as gentle as I wanted to be this year, that I didn’t train the dog to heel, or run a marathon or build more things out of Legos. I am disappointed I am not as patient, or even as kind as I thought I was. But this I can do: I can sit on the back step and turn my palms up to the spring night, revealing a slender frond of green, reluctantly raising its head above the earth.

Inside, I can hear the boys playing still, giggling in a sweet, “let’s prolong bedtime” sort of way. But my palms are still turned up even as the night is falling down over the day. Evening being the way spring is: stuck between the seasons, wedged between cigarettes and incense, medicine and mantra, sin and the ways we are saved.

Ice

February 24, 2015 § 31 Comments

Maybe what cold is, is the time we measure the love we have always had, secretly, for our own bones. – Mary Oliver

The first snow flakes were half-hearted. I reminded myself I am so far below the Mason Dixon line that any snow here would be a fluke. And then the flakes got fatter and faster. By the time I folded some laundry and emptied the dishwasher, snow was definitely lining the porch railings. Even me – with my ability to bury my head in the sand – couldn’t deny the ground was white.

School had been closed before the snow even started, and the boys dug through a box of hats and gloves in the closet and went out with their friends, all of them off to the sledding hill and dragging their summer boogie boards behind them, the leashes improbably being used as tobaggon handles. The dog came out with me and spun and danced and tried to eat the freezing rain as it fell. We were out for so long I could no longer feel my face and Wags’ coat became frozen and clumped in sections. I remembered one of the things I comforted myself with during the scorching days of summer was that at least, living in North Carolina meant I wouldn’t have to walk around with ice in my hair during the winter. But it turns out I was wrong about that. It was like the sweet thought I had on my wedding day, that having a husband meant I would never be alone again.

Scott has been gone for nine months now, and I am weary. I feel ancient. I had thought the initial sadness and missing him would pass but it hasn’t. He is still gone and I see now he is the roots to my waving branches. When he was home for Christmas I felt everything settle, the way it does after an earthquake. When I woke up at night, I heard his breathing, and in the morning, he made coffee calmly and methodically – without pausing between scoops to make oatmeal or get water for the dog or take a handful of vitamins, the way I do.

Now I am back to being alone and waiting for the real mom to show up, the expert who knows what to do when my son says “NO!” and the kids at school are forming cliques, and the teacher assigns those ridiculous word problems. Most days, I can fake it well enough that the veneer holds. I pack the lunches and uncrumple the homework. I dole out as many hugs as I can and sweep up the piles of leaves and bark that always fall out of Gus’ pockets. I try not to freak out when I get frustrated. I drive back and forth to the gym to teach yoga, but lately, I have been feeling like a fraud. I keep thinking that it shouldn’t be me up in the front of the room because I am just about certain that everyone can hear the anxiety and sadness and apathy clanking behind me like tin cans on a string.

Walking in the cold with the dog this morning, I listened to the particular silence of snow which is the exact sound of being alone. WIth Scott gone, I have been forced to look at the tree without leaves, the bare ground without a tropical swath of color, the grey sky without its oppulance of blue. My eyes have been turned towards all of those lonely and vast spaces inside, all of those corners haunted by self-doubt and fear and the smoldering ashes of anger’s old fire. When Scott was here, I had distractions and we had plans. I didn’t have the long stretch of bedtime to test my patience or the dark nights to mock my courage.

Now, I am like the tree in the front yard dropping icicles. These parts of myself I had thought were so solid are now showing themselves as brittle costumes, and it’s like that rotten old dream, the one where I have no clothes and am trying to hide behind a parking meter. My diet is irratic and inconsistent, sometimes consisting of food people normally turn into meals, and other days, I alternate green smoothies with bites of chocolate. Dinner is sometimes peanut butter on a pear and other times, a bowl full of pasta. I am still meditating consistently but I am hardly practicing yoga, sometimes managing 54 minutes, but never an hour. I tell myself it’s because my shoulder hurts, and this is somewhat true, but it’s a deeper frustration, a fear that there are some things yoga can’t fix.

Next week, an orthopedist is going to finally cut into my rotator cuff and fix the tear there, and I feel a mix of terror at the nakednes of it all and relief, that finally – maybe – the ache behind my heart will be repaired, that once again, I will be able to do a chatarunga and lift my arm over my head without the pinch of pain and the somber reminder of my impassable limits. I will be under anesthesia and then in a sling, forbidden for weeks to drive or write or chop carrots. It is both mortifying and terrifying to give up these central pillars of control, and yet, it also feels like sliding deeper into the stillness I entered months ago, a winter that has nothing to do with the ice outside.

This afternoon the boys came inside with a friend and I became swept up in the wonderful familiarity of trying to make food quickly enough to keep pace with their ravenous appetites. I listened to them talk about Legos while cutting apples and making hot chocolate and cleaning puddles of melting snow from the floor. When the kitchen was filled with their loud voices I felt like myself again – that person I was so sure I was. But then they ran upstairs to build a new Lego base, and it was quiet again – just me in the room listening to the freezing rain hit the windows. I watched as a curl of panic rose up like a specter and began to claw at the edges of the silence. The frightened ghost was me and not me. Maybe she is a piece of me, in a bathing suit, crouching behind a parking meter, trying to hide from the cold.

In December, in one of my yoga classes, I talked about the Celtic goddess Calilleach, who rules winter. She is a hooded old crone with perfect eyesight who freezes the ground with her staff and drops stones from her apron to form hills and mountains. I have been thinking about her again now, about her sharp discernment and her ability to lay the burden of her burdens down, allowing those heavy stones to slip from her pockets and fall. Without fanfare or nostalgia, she drops them, exposing them to the harsh winds of winter, and allows them to be shaped into something beautiful.

Responsible

January 10, 2015 § 23 Comments

Forget saftey. Live where you fear to live. – Rumi

We have a new crossing guard at school. The old one was very friendly but he was also ambivialent, and I was never quite sure whether it was OK to keep driving or if a bunch of kids was going to jump out into the street in front of my car. This new guard is different. He is emphatic. He steps out into the crosswalk with his sign held high and his hand out. Stop, his entire body says. Yesterday, as he glared out at our line of cars and shepherded the children between sidewalks, I breathed a sigh of relief. I hadn’t realized how vigilant I had to be with the old guard, when it seemed as if no one was really in charge.

Teaching yoga is not natural for me. When I practice and go to someone else’s class, I plant myself solidly in the middle of the room so I am surrounded, anonymous, and invisible. Sitting in the front to teach is a bit terrifying and so far, it hasn’t gotten any easier. I love being told what to do, how to move, and when to breathe, but playing the role of leader is miles out of my comfort zone. “Breathe in,” I say when I teach, and am shocked when I hear people inhale.

On the weekends, when it’s just the boys and me, I sometimes catch myself waiting for the real grownup to arrive and take over. I have moments when I feel just as I did when we took Oliver home from the birth center where he was born. “They’re trusting us with him?” I kept asking Scott, who had the same panicked look on his face.

Lately, the new responsibilities in my life are overwhelming in a way that makes me feel kind of loser-ish. A few months ago, I expressed my leadership concerns to Rolf and he told me we are at our best when we are giving one hundred percent but still feel stretched. And this is how I feel every day: stretched and still falling short.

When Scott came home from Bahrain for three weeks this Christmas, I was so tired I could barely get out of bed for the first two days. I hadn’t realized how exhausted I was, how difficult it is for me to be in charge, whether it’s in the six yoga classes I teach or at home, as the solo parent. And yet, that is precisely my role right now: to be the responsible one. To be a shepherd of sorts, ferrying my crew from one pose to the next, trusting that right action will arise for all of us.

So many of my friends glide into leadership roles seamlessly. One owns her own law firm, another her own business, and on this Marine base, I am surrounded by some of the strongest and most together women I have ever met. It’s been humbling to realize how different I am and that what comes easily to them is elusive to me.

Rolf conned convinced me to help lead his 200 hour yoga teacher training here, on Camp Lejeune, which is he offering free of charge to veterans. Most of the guys in the training also take my yoga classes, and this has raised the bar even higher for me. The 200 hour training meets once a month and Rolf dials in, appearing on the big TV screen in the yoga studio. But there in the room, I am the one in the front, the one being watched, not just in the training, but daily as I live and teach, succeeding and failing in various degrees. Like a butterfly pinned to a board, I feel exposed, and more than a little bit fragile, my own wings feeling dry and brittle.

And yet, stepping out of my comfort zone to this degree – doing what is so radically uncomfortable – has pushed me to take unusual steps. Knowing that I am being pushed in new directions has brought a new level of accountability to how I sequence my classes and to how I live. It’s so obvious to me now the areas in which I am out of alignment as a teacher, a parent, and as a person. I have had to take charge – and make changes – if not willingly, then by necessity, whether it’s encouraging my children through transitions as Scott leaves again for another five months or ushering students through a yoga class. Most of this is a two-step forward one-step back kind of thing. I feel a measure of success and then I lose patience, my sense of timing, or my nerve.

Breathe in and know you are breathing in, I say, as Rolf taught me to do. And breathe out and know you are breathing out. I am acting “as if” and hoping that some day, who I am now will catch up to who I want to be.

Boone

November 28, 2014 § 27 Comments

When it’s time to move on, there is no one to hold your hand. – Deb Talen, Ashes on Your Eyes

All I knew was that I couldn’t handle Thanksgiving this year. Fourth of July nearly did me in. It seemed as if every dad in the world was manning a grill or out in the driveway fixing something. One of my neighbors was in his garage blasting country music from his F150, and I felt oddly unprotected, even though I couldn’t identify the threat. The cicadas were whirring, the puppy was curled next to me, and the sun was reassuringly hot. Trying to keep things normal, we rode our bikes to the pool- that special summer domain ruled by stay at home moms and kids.

But even that was ruined with men. I sat on the edge of the pool with my sunglasses on while the boys jumped in. Nearby, a general’s wife was giggling and handing out paper cups of wine in a way that reminded me too much of high school. Later, the boys played with a neighbor on a slip and slide and then ran up the driveway with sparklers. The mosquitoes were fierce and I was panicky with a loneliness that was dark enough to feel dangerous. In my head, I mentally ticked off the holiday weekends that remained. Not Thanksgiving, I thought. There is no freaking way.

Last month, I booked a cabin in Boone, North Carolina for this weekend, an extravagant purchase that left me weak with relief. Until Tuesday night, that is, when I cursed my decision. After a busy week, I was finally throwing fleeces and underwear into a suitcase, trying to find large enough mittens and warm enough socks. My neighbor brought over snow pants and I was shocked to discover Oliver is big enough to wear my old hiking boots. Despite the fact that we were leaving, the same panic that haunted me in July was tugging at my ankles; the same creeping loneliness was draping its arms around my neck. I packed and cleaned until almost midnight and then loaded up the car with board games and down coats, suitcases and dog toys.

How foolish I was, thinking I could outrun a holiday.

Still, we got into the car Wednesday even though it was raining so hard, some cars were driving with their hazards on. After only a few miles, I was hunched over the steering wheel, wondering how this was all going to work.

By now, this is a familiar question, one I ask myself daily as I struggle with patience at bedtime or sit in the front of the room before a yoga class I am about to teach. So much of teaching is about being vulnerable, about walking into an empty space and hoping things are going to work out.

On Wednesday after I loaded the boys and the dog and the pretzels and the pears, we stopped at Starbucks. I had been too wiped out to make breakfast and the kitchen was too clean. We ran through the rain, and inside, the smell of coffee was a warm comfort. It was crowded and happy with that pre-holiday hopefulness, that maybe, this year, things would be better. I didn’t hear a woman calling my name until she grabbed my arm and said “Hey you!” It was Terri, a woman who works out at the gym the same time I teach yoga. She is small and wiry with spiky grey hair and eyes the color of sea glass. She was sitting with her friend Maria.

“Oh, these are your boys,” Maria said, touching my arm and smiling. “My girls are all coming home this year.”

“All four girls,” Terri added. “They live in New York. And oh my god – Maria is the best cook. Everything she makes.”

Maria smiled modestly and told me her husband was just home from deployment and that for the first time in a long time they would all be together. I felt her joy beginning to warm through my cold hands and feet.

“You have to try her carrot cake,” Terri said. “Oh my god, I will never eat carrot cake from anywhere else ever again.”

“Are you traveling?” Maria asked me and I said we were on our way.

“Is your husband here?” Terri asked and once again, I felt that shock that I am now part of this community, one that knows what it’s like to not know what will come next.

Last month, my neighbor was almost in tears because her husband was going on yet another training exercise to prepare for his deployment in August. “He’s going to miss Halloween for the fourth year in a row,” she said. “I’m so tired of this. I just want a normal life.”

“I know,” I said, and felt the familiar longing for predictability, agency, and home. Last week, Scott called and told me he just spoke to his detailer – the person who tells him what and where his next job will be. For five years we have been trying to get back to the west coast, and each time, we get farther away from my idea of home. I miss California so keenly, it feels like a phantom limb.

“Well, “ Scott had said. “It’s now between San Diego and one other place.”

“Oh jeez,” I said, because it’s always been between California and one other place. And we always go to that other place. “So San Diego or -?”

“Guam,” Scott said and inside, my mind said I can’t live in Guam. It will be a disaster. And then I remember that it will probably be fine. Because it’s always been fine, at least after a little while, anyway.

“We’ll find out soon,” he said. “I’m pushing for California.” But we both know it’s mostly out of our hands.

I told Terri Scott was in Bahrain and we were running away to Boone. Terri gave me a high-five. “You’re breaking the mold girl! Good for you.”

As we left the store, an older man with a rain-spattered Life is Good shirt held open the door for us and we stood under the outside awning, watching the rain bounce on the pavement.

I did not yet know what the day would bring. I had no idea that outside of Durham, I would drive through a soup of fog and truck spray and rain or that outside Charlotte, the skies would clear, revealing a ragged V of geese. I didn’t know I would stop for gas in a place so scary, it was like something from a Stephen King novel or that the flat land of eastern North Carolina would be so comforting: the low cotton fields and the leaning shacks; the plywood signs announcing boiled peanuts and sweet corn and “tomatos.” (They always forget the “e”). I didn’t yet know that our cabin would be snug and warm and I didn’t know that Wags would be so scared of the stairs I would have to carry her up and down every time we took her out. I didn’t know that for the first time, I wouldn’t get lost, that we would find the hiking trail I read about online and that it would snow as if on cue. I hadn’t yet discovered that pumpkin pie and hot chocolate were the only Thanksgiving foods we would need and that all the things I thought were so important would turn out not to matter very much after all.

Then, I only saw that it was raining hard. I only hoped things were going to work out. I only knew I had been trying really hard to run away from things that are impossible to avoid. Thanksgiving, deployment, the unknown.

“Wait here,” I said to the boys, “And I’ll bring the car around so you won’t get wet.”

“No,” they both said, protesting loudly.

“OK,” I said, watching the rain slant sideways in the wind. “We’d better go.” I took their hands and we ran towards the car, towards the mountains, towards the day.

One

June 30, 2014 § 40 Comments

Don’t let fatigue make a coward out of you – Steve Prefontaine

It’s been over a month since Scott left for Bahrain and June has been like most other Junes. And it’s been like nothing else I have ever experienced. The end of May seems ages ago, and yet, here we are, already sliding into July. We have navigated a trifecta of holidays without Scott: Memorial Day, Father’s Day, and our ninth wedding anniversary. Gus graduated from preschool, the boys began another round of swim lessons, and Oliver fell at a birthday party and needed his face glued back together. We got a puppy (more on that later) and I fixed the internet after a storm blew it out. I take out the trash now and lug those huge water bottles onto the cooler and send in the bills. I have stacks of unread books and blogs but I drove to Pennsylvania and back, where I saw a Mennonite man in Walmart. He reminded me so much of myself in the way he looked out of place, the mud on his boots coming from another time altogether.

Like most anything that can be anticipated, this first month of deployment was both harder and easier than I imagined. As my friend Lindsey writes, “My life is exactly as I planned it and nothing like I expected.”

Scott’s leaving left a gap in my own life, a rabbit hole, where I have been tunneling between my old life and this new and different world. I have solitude to contend with now and a heightened sense of responsibility which lays across my shoulders like a fur robe. Sometimes, it is heavy and grave, and other times, it’s a rich privilege to be reminded of my own capabilities.

I was single for many years, but since I have gotten married, I have abnegated so many responsibilities, maybe even responsibility for my own life. It’s so easy to call into the other room that the internet is down, that the sink is being weird, that I don’t know how to print out my insurance card, that I shouldn’t bother trying to do anything with my life because I’m just going to move again in two years.

This has been sobering.

It’s so easy to be powerless and to blame – to say if only – to imagine that someone or something is keeping you from something. And it’s now both embarrassing and liberating to realize that that someone was me.

Over the past few years, I have taken the wife role so seriously: The laundry and the cooking and the work events that felt so mandatory. Now that it’s only me, I see how so much of that nonsense is optional and that I really do have a say, even if it’s only to say screw it.

The week after Scott left, all three of us were exhausted and staggered through our days with a varying degree of tears (sometimes mine). We have been able to FaceTime with Scott almost daily, if only for a few minutes, and this seems to satisfy Gus, who holds the phone over his Lego creations and his Lego man and says, “This part is where he keeps his gems, this red piece is the control panel, and this piece here is left over from Oliver’s Thunder Driller,” until Oliver begins to yell that now it’s his turn and Gus has had enough time.

Saturdays are the hardest. Scott used to take the boys for most of the day while I drove 90 minutes to a yoga studio or simply did errands. Now Saturdays are glum and Oliver is usually in a foul mood. This Saturday I had the terrible idea of trying to replicate the “Daddy Days.” I made cinnamon rolls and took the boys rock climbing, and by noon, all of us were yelling. My friend Alana coined the term “coming out sideways,” and this is how Oliver’s – and my own – feelings are being expressed.

I have been heartened lately by thoughts of distance running, which I can’t do anymore but which I did for many years starting with my first cross country race when I was eight. In college, cross country races were about three miles, and the first mile was always the most difficult for me. While I could run one pace for a long time, I had no natural speed. To even get a half-decent position by the middle of the race, I had to take off from the start as if lions were chasing me, dodging the melee of elbows and hair ribbons, pony tails and spikes. By the time I made it to mile two, my breath was thin and ragged, my stride uneven, and I felt about as shredded as I do now.

Joanie Benoit once said that the key to racing is to find your pace, and then find your place in the pack and get comfortable there. I have been thinking about this advice a lot, thinking that maybe it’s OK that I end most of my days feeling weak and shredded, because this is what mile one looks like. I remember the way my breath came back in mile two – two footfalls per inhale – and hope that tomorrow I will hit my stride and the footing will be better. I am trying to be patient, both with myself and with my boys. I am trying to do less and slow down more, which is difficult for someone who is used to running, if not fast, then constantly.

When I look back on June, I’ll remember that we got through, but just barely. And yet, what an interesting time this is, like one of those bizarre social experiments from the seventies: What happens to a traditional stay at home wife when you take away the husband?

As of now, I have no idea, but it feels like something of a privilege, if a hard-earned one. Lindsey and Aidan have been writing about marriage this June, and I think it’s kind of a wonder to have a 12-month separation that isn’t due to unhappiness. I have a marriage sabbatical, or maybe a marriage retreat, and I am intrigued by this idea of hunkering down and peeling off the traditional garb I was never very good at anyway. I am clueless as to what the next eleven (gasp!) months will bring, but it’s still early in the race. We’re still finding our pace.

Stitches

June 18, 2014 § 37 Comments

“Have faith in the way things are. Love the world as your self; then you can care for all things.” – Lao Tzu

I was right in front of Oliver when he fell. I was sitting in my friend Jill’s gazebo taking a bite of watermelon at her son’s ninth birthday party as Oliver ran towards us. He and all of the boys were still in their bathing suits but had moved out of the pool and were now playing a complicated game of tag. Or maybe it was hide and seek. Oliver was running as if he was going to hide in the bushes around the gazebo, but he slipped on some dry leaves, and his face hit the wooden step. I jumped up and ran around behind him, but Jill reached out her arms and pulled Oliver up through the bushes, the gash on his face open like a second mouth. “Let me get Jon,” Jill said and handed me a beach towel.

Jill’s husband is a Navy doctor, and after what seemed like a long time, he walked over to us and calmly removed my shaking hand from the towel I was pressing into Oliver’s face. “Let me take a look at that.” After he replaced the towel he said, “Well, you can take him to the ER or I can take care of it here.” Sweat was dripping from Jon’s face. I looked down at his sneakers and realized Jill must have found him during his run.

“I want to stay here,” Oliver said.

Jill shrugged. “If it were our kid, we definitely wouldn’t go to the ER.”

Five minutes later we were sitting in their air conditioned kitchen while Jon dabbed at Oliver’s wound with Q-tips and unwrapped a package of Dermabond. “I’m going to teach you how to breathe while I do this,” Jon had said before he began, and I watched while together, he and Oliver inhaled and exhaled slowly, my own chest rising and falling, my own heart beginning to slow down.

“You’re doing great, buddy,” he told Oliver as he dripped hydrogen peroxide into the gash. “I’ve worked on Marines who yell and scream when I do this.” Oliver closed his eyes and squeezed my hand, and I had to look away and gulp air through my mouth. Last year, Jon returned from a deployment near the Helmand Province, an area rife with both insurgents and IEDs. Jon is an orthopedist, and I didn’t want to think about the injuries he saw there.

“You all made it back from Afghanistan, right?” I asked Jon after Oliver had been patched up and was proudly showing the other boys his bandage.

“The medical corps all came home,” he answered. “But not all the Marines.”

Most days, as I cut peanut butter sandwiches in half, pull weeds from the tomato beds, sit in my friend’s bright kitchen as she dumps the watermelon rinds from a birthday party into the trash, I often forget I am tied to the military, even as artillery booms across the water and helicopters fly overhead. This war has been going on for so long that I am numb to the stories, as if they belong to someone else’s life or to another world completely. And then something happens – another civil war, another battle for Falluja, another story from a friend or neighbor – and I realize that closing my eyes doesn’t mean things stop happening.

Perhaps the biggest impact of Scott living in Bahrain is that the stories I used to think were relegated to an imaginary world are now intertwined with my own. I am too aware that things I thought only existed on the news are actually happening in my lifetime, in real time.

When I do Facetime with Scott, I sometimes see the Manama skyline from his hotel, the industrial, unfinished city and the sand surrounding it. He is apartment hunting now, and in the photos he sends, I can see the Persian Gulf from a window over the kitchen island or sometimes from the bedroom. Water view, he types underneath, as if he is trying to sell me on the place.

Last week, Scott told me about a brief he had to attend about Ramadan, in which he was reminded he could not eat or drink in public and that he was required to wear long sleeves and pants. Ramadan, I think, and remember a friend who left Afghanistan in the 1980s, as a child, because her father was a Freedom Fighter. During one Ramadan right after college, I had my first chai tea in her tiny apartment while she told me about the meals her grandmother used to cook when it was time to eat again.

For so long, I have lived in small, narrow rooms, consumed by my own private joys or struggles, or simply the questions of what color pawn I want to be, when we are going to the pool, what we are having for dinner. I like being insulated like this, safe as houses. In fact, I long for a permanent home of my own with a keen and insistent wanting. I can’t wait until we can stop moving every two years like bedouin. Maybe I am even a little bit obsessed as I cut photos out of magazines, pour over Pottery Barn catalogs, and sometimes take paint swatches from Lowe’s, as if I had rooms to swath in color. So it’s probably no accident that each place I have lived has taken me further from my ideal of home, to the point where our family is no longer even together on the same continent.

My friend Christa once told me we keep getting the experiences we need until we learn the lessons, and I believe this may be true. A few months ago I read an interview by Chip Hartranft in which he defined abhyasa – traditionally translated as practice – as to sit and face what is real. When I told Rolf about this during my training, he said, “To sit and face what is real and allow it to be exactly as it is.” This may be the central lesson of my life right now: Can I keep my eyes open and let things be? Can I have faith in the way things are?

Oliver’s bandage fell off a few nights ago, which was a relief because it had gotten pretty gross. He was wearing only his pajama bottoms when he came to find me brushing my teeth, and he had to drag a step stool over to see himself in the bathroom mirror. The scar on the top of his cheekbone was small and neat, another stitch in the fabric of himself, holding together the being and the becoming. He turned from side to side, his torso lean and fragile. “You know Mommy,” he said with a big grin, “I think it looks pretty good.”

Unraveling

May 26, 2014 § 22 Comments

If I were out at sea, I’d want to know someone was waiting for me, wouldn’t you? – from “Seating Arrangements” by Maggie Shipstead

When I first read The Odyssey, in ninth grade, I thought that Penelope was a bit of a drag with her weeping and begging to be put out of her misery. I smugly thought I knew what she was doing, spending her nights unraveling the shroud she had been weaving all day in order to keep her suitors at bay. There didn’t seem to be anything more to it. The only reason I even remember the class at all is because it was where I first learned about symbolism, which felt a bit like opening a secret door.

Now, I see Penelope’s sabotaged weaving as something much different. I see the unraveling as something that happens when a person physically leaves a marriage, no matter how much love or faith remains. Until Scott left for Bahrain, I hadn’t realized how much a marriage depends on both threads, woven together in words and shared experiences and in presence. I had taken for granted the way Scott and I can look at each other and smile (or grimace) at something Oliver or Gus says, however innocuous, because it conjures up a shared, but private history. Frankly, I am surprised by this, by how I have allowed myself to become so entwined in another person’s life. For 32 years I was single, and mostly unattached. Naively, I had thought I could be in a marriage but keep my solitude and independence, that I could create a life with someone but not miss them too much if they went away.

Scott works long hours normally, and during April and May, he was gone before sunrise and often came home after dark. While I knew the weekends would be difficult, I didn’t think this deployment would make much of a change to my weeks. I had thought I was stronger than I am and I am completely caught off guard by how much I miss Scott, how much I depend on his steadiness, his sense of humor, and the ways he allows me to completely fall apart.

Now, he is living in a hotel room in Manama (it might be months before an apartment can be obtained because of security clearances) and he can Facetime with us in a computer lounge on base. He calls in the mornings or in the afternoons here, which in Bahrain, is after 10 pm. He sends beautiful emails detailing the delicious shawarma dishes he eats, the fresh fruit juices on the menu instead of cocktails, the rug shops that are open until late at night. “When you visit,” he says, “We can pick one out.” I think of those thick and colorful tapestries, and I feel myself coming undone.

Scott told me that the international school where we would have sent the boys is on the edge of a Shia village, or a black zone, forbidden to Americans because of sectarian violence. He told me about the big fence around the school and the graffiti on the walls, the armed guards who ride on the school buses. On one of his first nights there, the street with American restaurants was closed because protesters were burning tires. Scott also sent beautiful photos of the Manama skyline sparkling at night, of the tan and empty desert, and the twin spires of the Grand Mosque, which my mother accurately pointed out, “look so much more interesting and exotic when they are in your own email box instead of in a magazine.” When I talk to him, I can almost feel the heat he describes or smell the bahji puri, but mostly, I just feel so far away.

My neighbor’s husband is in Guantanamo Bay for nine months, and the other day, while she was walking her dog, she warned me the weekends are the worst, and this holiday weekend proved her right. Oliver has been extremely difficult lately, both needy and angry, and I am trying to be understanding while also holding the line that must be held for him. Of course, I am flooded with doubt over every decision. Oliver loves boundaries even as he rails against them, making faces at me, talking back, telling me he doesn’t care that he has lost his screen time. In a single day, I am both the meanest mom on the planet and the best mom in the world.

Today, we drove 90 minutes to Wilmington, mostly because I couldn’t stand the sight of one more father firing up a grill and because I was feeling angry and needy myself. We went to a historical, working plantation and then to a children’s museum. “I know you’re having a hard time,” I told Oliver, after I made him sit down because he wouldn’t leave his brother alone. He looked at me with his father’s eyes and said, “It feels like a piece of my heart fell down into my stomach.”

Jason Crandell, the yoga teacher, recently posted this on Facebook: “Your edge is the threshold in a pose—or moment in seated meditation—where physical, mental, and emotional resistance comes rushing to the foreground. Reaching your edge is like applying an enzyme that ignites a reaction and magnifies your physical, mental and emotional patterns.”

This leaving has revealed a jagged edge I didn’t even know was there. I didn’t realize my husband’s journey across an ocean would dredge up all the other times I had been left, and even worse, the magnification of all the ways I abandon myself. I hadn’t known this fact about myself, which is that my constant doing might become my own undoing, that I don’t really know how to stop, how to be still, how to let go. I know how to fill a space with yoga or reading or meditation or watching TV, but this is wildly different from doing nothing or becoming empty.

For the first few nights Scott was gone, I didn’t really sleep. As another dawn began to leak through the night, I felt as though vines were wrapping themselves tighter and tighter around my chest. Already, I was thinking of cleaning the house, going on another cleanse, doing a 40-day meditation sadhana. I know how to tighten and how to restrict. I know how to take away and how to cleave at the messiness until I am clean and sharp. But as I lay there, listening to the buzzing satin of the dawn, it became clear that while I know how to fall apart, I have no idea how to unravel.

Images have been in my mind and heart lately: kelp fronds waving in cold oceans, wind chimes untwisting in the wind, the line from the Tao te Ching that reminds me to have faith in the way things are. I don’t yet have enough faith to believe that everything happens for a reason. There is too much darkness in the world for me to believe in both this and a benevolent god. But I have a sense that in my own good life, I am getting lessons I need to learn. Today, in the plantation, we peered into a weaving studio with a spinning wheel and a loom. Outside, sheep grazed and inside the wool was carded. Fabric was woven together and dyed and sewn into something that can be worn. And yet, I was focused on the undoing of it all, the unweaving, and the unraveling, and what it might feel like, when I too learn how to twist and untwist in the wind.

Care (Again)

May 9, 2014 § 3 Comments

Compassion is not a relationship between the healer and the wounded. It’s a relationship between equals. – Pema Chodron

Thank you so much for all of your comments about what self-care means to you. I learned more from your comments than from any self-help book. If you haven’t read them, you can find them here.

I am bolting in a different and good kind of way today and am in Chicago where I am meeting two of my oldest and dearest friends, both of whom live in the chilly Midwest. Since it’s already been in the 90’s in North Carolina, I have been surprised by the trees here, with their small and early leaves. As the cab left the airport and lurched into traffic, the new green here slayed me for a moment with its lesson of vulnerability that lately, seems to be at the heart of everything.

There is only one way to fly out of Jacksonville, North Carolina, and it is on the tiniest of airplanes. Today it was me and about one hundred Marines, all of us walking across the tarmac and squinting our eyes against the wind of the engines. Once I was on board in my miniature seat, it was clear that there was a mix-up with some tickets, as two people were claiming a single seat as their own. The Marine next to me calmly stood up (ducking his head) and said, “Why don’t you move, sir,” to the man who had taken someone’s seat because someone else was in his. When the man ignored him, the Marine tapped him on the shoulder, his tattooed bicep just inches from my face. “Sir, it started with you, why don’t you go back to your seat and let’s figure this out.”

The man in the black suit looked startled and then annoyed and then after the Marine calmly blinked at him, the man in the suit walked back to his seat. The Marine reminded me of my husband, of the way he can diffuse a situation without raising his voice, which is a special kind of power in this world.

“Nice work,” I said to the Marine next to me and he smiled.

“Just sorting out problems,” he said, as if he did this every day, which he probably does. He held my gaze in a way that unnerved me. Usually I face forward in airplanes. When flying, I do not make eye contact with anyone. Ever. And this sudden intimacy with a stranger was both unsettling and comforting. He had the same color eyes as me and for an instant, I wondered if we had met previously. And then, I realized that what I was experiencing was simply the recognition of our shared human contract, both of us alive to do something in the world.

This is the same feeling I had as I read your comments on what self-care means to you. Although I have not met most of you in person, I had the feeling that there is something deeply known in each of you, something deeply familiar and comforting and shared.

Thank you.

I will announce the winner of the giveaway on Mother’s Day.

Care – And Giveaway!

May 8, 2014 § 43 Comments

You too have come into the world to do this, to go easy, to be filled with light, and to shine – Mary Oliver, from “When I Am Among The Trees”

The last few weeks were big ones in our house. Scott finished his job (which has the best title in the world) as the Officer in Charge of Construction at the Office in Charge of Construction. (And who said the military has no imagination?) On Tuesday, they had a ceremony to disestablish the OICC, as the majority of work has been completed. What they did in a few years was outstanding. Roads, highways, and bridges, barracks, and fitness centers were built, totaling over three billion dollars. Scott’s family came out to visit from Oregon, his brother came from Texas, and my parents came from Pennsylvania. We rented a house by the beach, where the five cousins dug in the sand and hunted for sharks’ teeth.

The ceremony was surprisingly emotional for me, and I couldn’t help but appreciate how the military commemorates the endings and beginnings of things. Now you are here. Next you will be there. There is no ambiguity.

During the past few weeks I have been filled with ambiguity, while at the same time, without my own usual rituals of yoga and meditation and walks by the water. I even stopped using my neti pot and drinking lemon water. It’s not surprising that I felt groundless for many days despite the joy of being with family.

I am participating in Renee Trudeau’s Year of Self Care Mother’s Day Giveaway, which is amazing (see below!). The invitation to participate came at a time when I was already thinking about self-care. I get the basics of self-care: eat well, sleep enough, exercise, and do things you love – even if I don’t always do those things.

What challenges me, are the more subtle aspects of self-care. I have been working with Alana Sheeren, and her energy work has been a transformational experience (I will write more about this later), and as a result, I am thinking more about how I talk to myself, what I believe about the world, and what I allow myself to have. I have been really struck by the fact that I can drink all the green smoothies in the world, but if I have no faith in myself, I will be miserable.

I have also been thinking of the ways we (of course, by we, I mean I) handle the hard things. Pema Chodron says, “Never underestimate the inclination to bolt,” and I have been well-aware of how I bolt. (More to come on this too).

I guess what I am wrestling with really, is how do we take care of ourselves when we don’t want to? How do we be gentle with ourselves when we don’t believe we deserve it? How do we speak kindly to ourselves after we have snapped at our children or let a friend down? How do we make time for ourselves when so many other people have bigger, more pressing problems than we do?

I would love to hear your comments about this, as I think we have all been in these places of wanting to crawl under the covers with a trashy magazine/bottle of wine/Clooney/pint of ice cream/other personal escape vehicle.

This giveaway is really amazing. I wrote a review about Renee Trudeau’s first book, “Nurturing the Soul of Your Family” here .

To participate in this giveaway, leave a comment below by May 10th on what self-care means to you, and you could receive a Self-Renewal Package which includes a copy of the beautifully illustrated, award winning books, The Mother’s Guide to Self-Renewal orNurturing the Soul of the Family and free registration to the Mother’s Guide to Self-Renewal Online Telecourse (a $125 total value) from nationally recognized life balance teacher, Renee Peterson Trudeau and Hopeful World Publishing. Additionally they¹ll be entered to win the $2700 Year-of-Self-Care Mother’s Day Giveaway. The giveaway is a week-long self-renewal retreat at the Omega Institute. I will pick the winner at random.

I am sorry I haven’t given you more time to enter. (I was also looking for shark’s teeth. And maybe I was bolting a bit too).

Process

April 7, 2014 § 26 Comments

You can talk about writing all day, you can think about the book you want to write, imagine what the finished product will feel like in you hands, but until you actually sit down day after day and bleed the thing out of you, you’ll never see a word. – Claire Bidwell Smith

I was extremely honored and also surprised when my dear friend Lindsey asked me to be part of a blog tour about the writing process. Honored because I love Lindsey’s work and respect her discipline to her craft, both in the precision of her writing and the frequency with which she posts on her blog. I was surprised because I don’t write very often and am not really the go-to person to talk about writing process. At first, I wasn’t sure if I could write about something that doesn’t exist, but the inquiry itself was extremely helpful and provided some much needed motivation.

1) What am I working on?

So this is a really humbling question because I am not working on anything other than mustering the courage to get to my laptop and actually write. There is a great deal of debris in the path – because that is the nature of the path – but mostly I am battling the loud voice booming who do you think you are. (Note: I actually just realized this now, as I wrote it down, so thank you Lindsey for inviting me to answer these daunting questions.)

What I would like to be working on are more blog posts. An idea for a novel simmers always in my mind, but because I am not writing down what the characters do or say on a daily basis, I am not sure that counts. Another goal I have is to write more about my experience as a mother and yoga teacher and military wife. Because these puzzle pieces often feel at odds with each other, I resist writing them down. Often, I resist the stillness needed to sit and write as well as the honest inquiry that’s a necessary part of the process. However, the more people I meet, the more I realize that most of us don’t quite fit together at the seams and that the large pieces that are marriage and motherhood and children and careers and relationships often have complex edges to them.

2) How does my work differ from others of its genre?

Again, humbling question. I am not sure my writing does differ from those in my genre, if those in my genre are women striving to appreciate both the dark and glittering moments of our days, to make meaning out of the mundane tasks of being an adult, and to find our place in a world that is wildly different from our expectations and maybe, exactly the way our parents warned us it would be. I definitely have more grammatical errors than most, that is for sure.

On another note, I write about military life from a slightly different vantage point, as I am much older than the typical military wife and I married my husband despite the fact that I used to believe that most people in the military were violent, right-wing, rednecks. Mostly what I write about is how this wildly absurd and ancient belief of mine is proved wrong on a daily basis. I also write about teaching and practicing yoga on a military installation in the South, and while I have tried, I haven’t found a ton of people who write about this.

3) Why do I write what I do?

When I DO write, I write about teaching yoga and living on a military base mostly because I am lonely or I want to make sense of something. And I am trying to make meaning about this unexpected life of mine. And, there are so many staggering bits of wonder and joy and tenderness observed every day that I want to preserve them somehow. The only way I can get past the who do you think you are demon is to remind myself that my greatest responsibility in this lifetime is not to squander it. Deepak Chopra said that our gifts to the world are usually found in our deepest desires. So I am trying to be faithful to this message that we need to follow our hearts, not just so we will find happiness, but because it is the sole reason we are here on the planet.

4) How does your writing process work?

Okay. This question is just funny. (sigh). My writing process begins with me thinking of something to write about on a run or during a yoga practice or on my mediation cushion. Then, about 2 weeks pass in which I do absolutely nothing and feel lousy about it. Next, I blow the dust away from the keyboard and try to remember my wordpress user name and password. Finally, I spend an evening staying up too late, and writing. Usually the next day, I erase everything and try again. The process continues from anywhere between three to seven days, at which point I give up and hit “publish.” It’s almost a given that I can’t sleep that night as I wonder why I discussed something so dull and really, I actually wrote that and made it available to strangers? Or even worse, to people who know me?

Writing is hard. And if you are even a tiny bit as neurotic as I am, the process will bring you to your knees.

I am so grateful to be a part of this blog tour as – because it always happens this way – I often don’t know what I know until I write it down. Please check back – as I did – to learn about the writing process of successful writers. I took notes!

Next week, the tour continues with Dana Talusani and Betsy Morro, two incredibly gifted writers and friends.

Elizabeth Marro was a journalist and freelance writer before she deserted the field to make money marketing and selling drugs. (The legal kind.) Since 2002, she has been weaning herself from the pharmaceutical industry and returning to her writing roots. Betsy and I used to be in a writing group together in San Diego, and I am eagerly awaiting the publication of her first novel, Casualties, the manuscript of which, I was luckily enough to read and be captivated by. Her freelance work can be found at LiteraryMama.com , San Diego Reader, Peninsula Beacon, Downtown News, among others.

Dana Talusani writes at the popular blog, The Kitchen Witch. She is a former teacher, writer and personal chef and now lives and writes in Colorado, where she lives with her husband and two girls. Recently, she was chosen to be part of the Boulder – Listen to Your Mother performance. I look forward to meeting Dana this summer, and for now, I have to settle for her heartbreaking and hilarious blog and her text messages, which remind me I am not as alone as I think I am.

Procrastination

April 3, 2014 § 34 Comments

I haven’t banished procrastination forever by writing about it, but the prospect of a public shaming turns out to be an excellent spur to keep going. – Adam Green, April, 2014 Vogue, “Late or Never?”

I was recently honored by Lindsey’s invitation to join the blog tour about The Writing Process, which I will do on Monday. I was also a bit chagrined, as I actually have no writing process (evidenced by how infrequently I post here). For as long as I can remember, I have wanted to be a writer. But, can you really be a writer if you don’t write?

On Monday, we left North Carolina for Legoland Florida, and I do what I always do at the airport and spend way too much money on fashion magazines (which is totally ludicrous as I live in Gap jeans, tee shirts, and Chuck Taylors). Regardless, I thoroughly enjoyed the recent Vogue piece by Adam Smith in which he honestly details his experience as a chronic procrastinator. After just narrowly making a deadline, he tries to alleviate some anxiety by surfing, only to come face to face with these questions about his inability to write:

“Did it stem from fear of failure? How about fear of success? Was I crippled by low self-esteem? Or did I withhold my best efforts because I thought that I was special and the world owed me a living?”

Yes to all. And also, None of These.

For me – like many other writers, and of course, Joan Didion who first said this – “I write entirely to find out what I am thinking, what I”m looking at, what I see, and what it means.”

Lately, I haven’t wanted to know what I am thinking. I haven’t wanted to feel much of anything. Lately, all I can think of is Scott’s upcoming deployment, which embarrasses me, because I am Too Old For That. We have been together for eleven years, and I should be a seasoned veteran at this point. This whole deployment business should be Old Hat. I should be like the Marine wives around me, the ones who wave their hands in the air when I ask how they are doing while their husbands are in Afghanistan, the ones who tell me that it’s fine, that they are used to it, that sometimes, its even easier.

This is not my experience. Right now, I watch Scott do the dishes and think that in another six weeks, he won’t be here to help with anything. Today, he replaced the battery in my car, and I thought, Lord help me. On Friday nights, as I sink into the couch with a glass of wine, I remind myself that when Scott leaves, I will need to be Sober At All Times, because I will be the only one in charge.

Rationally, I know that Scott is leaving because his job demands it and I knew this going in. And yet, it feels a lot like being abandoned. Waiting for him to pack his bags and go reminds me of all the other times I have been left, even if now I am grateful that all those people are no longer around. There is something about standing still that feels like falling behind, and some days, it causes me to put a hand on my heart and take a breath.

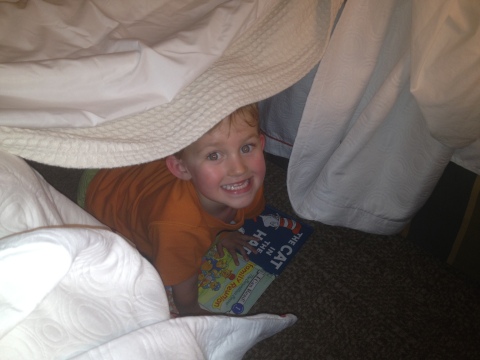

This leaving that we are all waiting for is affecting the boys too, or at least Oliver. It’s common in the military to be told that if the mother is fine, everyone is fine. Maybe this is true. And maybe, kids have their own feelings about things. I haven’t written much about my children lately, because life at home has been challenging. I haven’t wanted to write about Oliver’s stubbornness, his defiance, his 8-year-old explosions. After a very difficult week, I took Oliver to lunch and to the bookstore and he told me he was sad his dad was leaving and a little mad too. “Why can’t they send someone else?” he asked while crossing his arms over his chest, and I did my best to explain that sometimes we are the Someone Else. At night, Oliver and I have been reading Harry Potter or The Secret Zoo series and as he snuggles against me. I remember that while I may be saying goodbye to a partner, he will be missing his dad.

The first day of Legoland wasn’t much easier than home has been. At the suggestion of going on a ride outside of Chima Land, Oliver shouted “NO!” or sulked, or crossed his arms over his chest. All of these reactions frustrated me immensely. He’s going to grow up thinking he’s entitled, I thought, or He’s spoiled or Here we are in Legoland and he can’t appreciate any of it. Scott and I exchanged many looks that day which said mostly the same thing: Be patient. Yes, I know this is hard. and Don’t lose your shit.

Recently, a dear friend and mentor reminded me that when parenting, the wise choice is to choose love over fear. Sometimes I can remember this and sometimes I can’t. After that first harrowing and hot day, our eyes exhausted by primary colors, we found a small Italian restaurant for dinner where they brought homemade foccacia to the table and bowls of pasta so hot we burned our tongues. Afterwards, we walked to the small lake behind the restaurant where I cautioned the boys to watch for alligators. Undaunted, they ran on, while above us, a large bird circled and cried so loudly we all stopped to watch as it careened on enormous wings over our heads.

“What kind of bird is that?” Gus asked.

“A peregrine falcon?” I wondered.

“It looks almost like some kind of eagle nest,” Scott said.

Finally, Oliver said, “Why don’t you do a search for “raptors” and “Lake Wales, Florida” on your phone?”

The quick iPhone search revealed that the bird was an osprey, which have survived habitat loss by nesting at the tops of dead trees, channel markers and abandoned telephone poles. Before we went back to our hotel, we watched the male circle again, his wings arched and his talons out. While he was circling, the female sat in the middle of their enormous nest, observing it all. Nature is chaotic, I thought. Love over fear.

The second day at Legoland was easier than the first. We picked a few rides to go on as a family and then realized that what the boys really wanted to do was examine the life-like cities and buildings of Miniland and play in the treehouse-like Forestmen’s Hideout. I kept thinking of the female on that nest, watching her mate circle and the people below her come too close. If life is teaching me anything, it is that most of my problems can be solved by just calming down. Being still. Choosing love over fear.

I used to think that “comfort” and “stillness” were wildly different things – comfort being synonymous with decadence while stillness was aligned with a more monastic quality. But now I am wondering if the two intersect. Maybe, comfort is even found most reliably in the act of being still, in not circling around a moment but rather, sitting fully inside it. Perhaps my own procrastination has to do with avoiding my turn being the Someone Else. Maybe not writing is the way I dig in my heels, cross my arms over my chest, and resist. And yet, resistance is cold. There is no comfort in a fight, but I am always heartened at how quickly comfort returns when I stop resisting the way things are. Warm nests. Hot pasta. Fashion magazines. Uncrossing our arms. Being still. Maybe they are just different versions of the same thing.

Play

February 4, 2014 § 5 Comments

I am very excited to be participating in the series: 28 Days of Play, hosted by Rachel Cedar of YouPlus2Parenting. Rachel is asking the intriguing and maybe even uncomfortable question: Do you play with your children?

Please join me today over at Rachel’s to read what I have been too reluctant to have ever shared with a parenting group.

You can also link to the series through an article about 28 Days of Play on the NBC/Today Show Website. While you are there, check out some of the other amazing writers who will be joining in 28 Days of Play. And check out Rachel’s parenting coaching from the heart.

To read Dana’s beautiful Day 1 essay, click here.

I would also love to hear from you. Do you play with your children?

41

January 28, 2014 § 30 Comments

The number forty is highly significant across all traditional faiths and esoteric philosophies. It symbolizes change – coming through a struggle and emerging on the other side more enlightened because of the experience. – Dr. Habib Sadeghi

Usually, I begin my yoga classes with child’s pose or a simple seated meditation, but really, meditation is too strong of a word. We breathe in. We breathe out. And inevitably, a Marine in the back of the class is trying so hard not to laugh out loud that he is silently shaking. Usually, I have to close my own eyes and press my lips together so that I don’t start laughing myself.

It’s always a bit awkward in the beginning when I’m asking them to come into cat cow pose and then downward facing dog. Some people are looking around and vigilance pulls up the chins of others. No one is breathing and you can feel the tension rising off bodies like steam.

Then I ask them to come into plank pose, and like magic, all the giggling stops. After about ten seconds in plank, the vibrations in the room begin to settle. After thirty seconds, the disparate streams of energy begin to gather. After a minute, the quiet comes down like a curtain falling.

I don’t have them hold plank to prove anything, or even to quiet the laughter. There is something so familiar about that pose for Marines and athletes – something almost comforting about being in a high push-up. And yet there is something else about plank that gets right to the heart of our own vulnerability. Maybe it’s that our pelvis wants to collapse in a way that would showcase our weakness. Maybe it’s that plank pose demands us to soften the space behind our hearts. Or maybe it’s the quiet of the pose itself, the stillness required to hold ourselves straight and stare at a single spot on the floor.

After plank pose, it’s different in the room. I can say inhale and 30 sets of lungs breathe in. I can say exhale and 30 sets of lungs breathe out. I can place my hands on someone’s shoulders and they no longer want to flinch.

It was my birthday this week and I have been thinking an awful lot about vulnerability. 41 is a year that lacks the spunk of the thirties but also the dire nature of that four-oh milestone. 41 is not yet old but definitely no longer young. 41 is a bit like jumping into the shallow end of a freezing cold pool and hopping up and down, your arms over your head. 41 is about being in it but just barely. It’s about stopping by the mirror and knowing that you still look much the same as you did at 20, but undeniably, your skin is thinner and creased. What is left may look the same, but it’s only a veneer of who you used to be, and soon that will be gone too, and the true self – the real face that reveals our own creased and softened souls – will emerge.

41 feels a lot like being in plank pose.

Most of my fortieth year was spent on my back, staring up at the clouds that seemed to be rushing by too quickly. Last winter, I woke up in the cold sweat of panic attacks and during this past summer, I couldn’t sleep. 40 required waking up to the fact that I was living in a way that was not sustainable, that I couldn’t forego rest anymore in the name of getting things done, that I needed to stop saying yes when I meant no, and that I desperately wanted to stop asking for permission. Chocolate and wine were no longer staving off that terrifying feeling of fragility, and the warning hum underneath was becoming so loud I felt a little crazy. Last year, a line from Hamlet wove its way into my days: I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams.

For 39 years, what I wanted more than anything was to be tough. I would rather be angry later than vulnerable now. It’s easier to be the master of my own fate than to place it into someone else’s palm and close their fingers around those thin shards of glass. I had thought that toughness would scare the fear away. But it turns out that fear stays anyway and makes you want to giggle. It makes you want to yell or run or it wakes you up in the middle of the night and squeezes at your heart.

People talk about vulnerability now as this great thing and I suppose it is. But what they don’t often tell you is that one part of vulnerability is to take a good and honest look at yourself, which feels a bit like sticking your head into the mouth of a monster. Asking the questions is only one part of the equation. It’s sitting still with the answers that’s the kicker. There is the way that I think I am in the world, and then there is the way I actually am.

Sometimes I wonder how on earth I became certified to teach yoga. Of all the experiences in my life, teaching renders me the most vulnerable. It feels like taking off my skin. Before each class I feel like Hanuman, when he ripped open his chest to show Ram his devotion. Ram, Ram, Ram beat his heart.

I am working with Rolf Gates on my 500 hour teacher training, and in our last meeting via Skype I shared some of my challenges with teaching, mostly, that I don’t feel I am up to the task. Rolf laughed after I was finished and said,”Welcome to your first ten years teaching yoga,” which I found oddly comforting. He could have easily been saying, Welcome to your forties. And then he told me that teaching is like pointing at the moon. What’s important, he said, is that our students understand the moon.

The way I see it, there is no way to understand the moon without first standing alone in the dark. There is no way to understand anything unless you pay attention to the way it waxes and wanes, to the way it turns its back to you or slips behind a cloud. The glow and the radiance: it’s only a fraction of what it really is.

About three years ago, I wrote that I felt as if I was on the precipice of something, but couldn’t see far enough down to know what it was. Now, I see that what I was gazing into was the mysterious space that houses our hearts. That my task is to simply crouch in the doorway and pay attention to the storm, to the call of the wind and the violent lashing of the branches. My job at 41 is to sit in the eye of the hurricane, rip open my heart, and listen.

Sankalpa

January 2, 2014 § 18 Comments

I always wonder what the world would be like if we all had the same intention, to focus more on love. I don’t know. It could be very awesome. – Britt Skrabanek

Ever since I was in college, I have gotten sick in November. In college, the day after cross-country season ended, I would come down with a sore throat, a cough, a stuffed nose. Last year, I had bronchitis. This year was mild. I caught a cold and lost my voice after I taught several yoga classes. For a week, I could only whisper. I could no longer yell upstairs to the boys to brush their teeth or stop fighting or to come down for dinner. Instead, I had to walk up the stairs and pantomime holding a fork up to my mouth or point to my throat and shrug. Most of the time, the boys acquiesced and came down to dinner or resolved their arguments, usually upon Oliver’s lead.

I felt extraordinarily calm all week, which is rare for me. At the bus stop, I just stood with the boys and waved to the other mothers. When Gus came home from school, we played Uno or we went down to the bay across the street and found driftwood and shells, secret trails to the water, and animal footprints. During the evening, I walked out the back door and watched the sun as it fell into the water, leaving a wake of purple and grey and orange. Because I didn’t feel terrific, I went to bed early, and the time on my meditation cushion was easier, less fraught with all I wished I hadn’t said. The week of the lost voice made me see how rarely I needed to speak, how much of what I usually say is just an extension of the chatter in my mind.

After several days, a haggard whisper came back and then a croak. The next Monday, after Gus came home from preschool, we were in his room putting away laundry and Legos. “Mommy,” he said, when I asked him to hand me some socks, “I am going to miss your lost voice when it’s back.”

“What?” I asked, “Why?”

“Well,” he said, “It’s just that you’re loud. You talk in a loud voice.”

When I told Scott he laughed. “You are loud,” he said. “I worry you don’t hear very well.”

After my voice came back, it was Thanksgiving, and then Christmas came after like a freight train. Oliver broke his leg and was miserable of course, his cast edging up to his thigh. He was unable to ride his bike or play soccer, and he and Gus began bickering in the afternoons. The holidays grabbed me around the ankles and tugged. There was so much to do, from Scott’s work parties to buying presents to spending 22 hours in the car driving to Pennsylvania and back.

This year, the holidays were loud.

On a Friday, right before the Solstice, I took Gus down to the water across the street at sunset, while Oliver stayed home with his crutches and a book. “Look Mommy,” Gus said and pointed to the sky, which was molten and darkening quickly. “It’s the wishing star.” We stood there, side by side, listening to the rat-a-tat-tat of artillery practice across the bay. A great blue heron flew out of a tree, stretched its wings over our heads, and echoed the staccato of gunfire with its own prehistoric squawk. For a moment, I felt as if there was no time, that it had ceased to exist or maybe just collapsed, all time layering itself upon itself, wringing out the important moments and ending up with a sunset.

After Christmas, I went through the usual foreboding prospect of choosing A Resolution. The lapsed Catholic in me still approaches events like this as if they were a kind of penance: a whipping strap with the hope of salvation attached. And then I read Britt’s blog about creating a Sankalpa instead. A Sankalpa is both an affirmation of our true spirit and a desire to remove the brambles which can prevent us from manifesting that deepest self. It is a nod to the fact that we are in a process of both being and becoming, it’s a rule to be followed before all other rules, a vow to adhere to our heart’s desire.

My heart’s desire is for more quiet. More sunsets. More silence. More conversations that mean something, that both press on the wound and ease the ache. More jokes and more laughter. More saying yes when I mean yes and no when I mean no. More eating sitting down. More walks on the beach, hunting for sea glass. More reading and more sleep.

When I think about it, my inability to be quiet is really an inability to be in a moment exactly as it is, to be with myself exactly how I am, to not shake my feelings around as if I am panning for gold, looking only for the good rocks, the ones that shine. Instead, my Sankalpa is to be quiet, to place the strainer down and plunge my hands into the cold and dusty water.

If you would like to continue the Sankalpa Britt suggested, I would love to hear about it in the comments.

Happy New Year!

Gratitude

November 27, 2013 § 15 Comments

“If you want to be surrounded by angels in your lifetime, then teach.” – Rolf Gates

I wasn’t going to write a Thanksgiving post, especially after Kitch reminded me that tis the season when “bloggers around the nation will begin storming the Interwebs with gratitude posts.” Usually during the holidays, I try to lay low, as some of you know. As Anne Lamott says, “It’s hard enough to keep your balance and and sense of humor during the rest of the year. But the next 30 days are Grad School.”

I really wanted to stay in hiding this week because last Friday I got my hair cut and highlighted to camouflage the gray hairs that are sneaking their way in. “Lowlights too?” the woman asked, and I told her sure, which turned out to be a terrible idea as was the decision to get my lip waxed. By the time I walked out of the salon, my hair had violet streaks in it and the next day, my lip broke out so badly, it now looks like I have a communicable disease on my face.

A few weeks ago, I downloaded Bon Appetit’s Thanksgiving app, thinking that I was going to win at Thanksgiving for a change. My parents are here and I am making my first Thanksgiving dinner since I was 29 and single. Back then, the wine mattered more than the turkey (which turned out bloody in the middle and burned on the wings). Now, I am anxious about attempting to recreate the magic that Thanksgiving was when I was young. My mother made it all look so easy. On Tuesday I made cranberry sauce and felt ahead of the game until I checked my Bon Appetit app. According to that calendar, I was supposed to have already made two pie crusts, par-baked my stuffing, and whipped up a roux for the gravy. It appeared that already, I was losing at this.

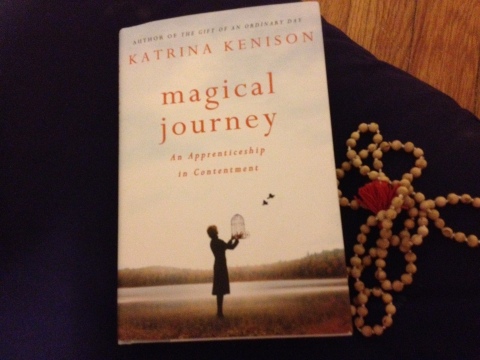

On Monday and Tuesday I teach two yoga classes each day, which I love, but still find daunting. Before each class, I worry that I will forget the flow, that I will not be helpful, that I will be wasting someone’s time. Yesterday evening I walked into class self-conscious about my face and my hair and slightly dismayed about my lack of Thanksgiving prowess. But as usual, the students changed my mood around, in the way that they always show up and do their best. During the spinal twists at the end of class, I read some of my favorite words of Katrina Kenison’s which I rediscovered yesterday on Claudia’s blog (and recopied below.)

After class, a young Marine stayed as he sometimes does to ask questions. Usually he asks me about poses I can’t do. Last week, he jumped up on the ballet barre and pushed himself into plank. “Can you teach me to do a handstand on this barre?” he asked.

“Um, no,” I said. “I’m still working on handstand on the floor.”

“My roommate and I,” he said in his slow drawl, “We’re in a competition to see who can do the coolest yoga shit.” Then he jumped up into a headstand and I almost had a heart attack.

When he came back to his feet I convinced him that maybe handstand was a better idea and I showed him some things to do on the wall. As he went up and down, he told me that what had brought him to yoga in the first place was a chiropractor who told him his lower back was so injured he might have to leave the Corps. “That dude was an idiot,” Carter told me. Then he explained that his spine was compressed from wearing a 50 pound flak jacket for so long. “Yoga is working though,” he said. “Look,” and he bent over and touched his toes. “I couldn’t do this a few months ago.”

Last night, instead of asking me to show him how to do a one-armed handstand or more “crazy yoga shit,” he told me he really liked what I read. He spread out his hands and looked up. “That part about feeling the earth and looking up at the sky?” He smiled with the lopsided grin and mischievous eyes that most 24-year old boys have but that older men tend to lose.

“What are you doing for Thanksgiving?” I asked as I powered down the sound system and locked up the headset.

“I’m going home,” he said. “Me and my roommate are going back to Kentucky.” He told me that his grandfather is terminally ill with ALS and his mom is going to bring Thanksgiving to him. “My grandfather is so great,” Carter said. “Since he’s been sick, he’s raised all this awareness about ALS and it’s going to be a special Thanksgiving. Plus,” he added, “I’ve been deployed for the last two Thanksgivings and Christmases, so just being home is pretty awesome.”