Responsible

January 10, 2015 § 23 Comments

Forget saftey. Live where you fear to live. – Rumi

We have a new crossing guard at school. The old one was very friendly but he was also ambivialent, and I was never quite sure whether it was OK to keep driving or if a bunch of kids was going to jump out into the street in front of my car. This new guard is different. He is emphatic. He steps out into the crosswalk with his sign held high and his hand out. Stop, his entire body says. Yesterday, as he glared out at our line of cars and shepherded the children between sidewalks, I breathed a sigh of relief. I hadn’t realized how vigilant I had to be with the old guard, when it seemed as if no one was really in charge.

Teaching yoga is not natural for me. When I practice and go to someone else’s class, I plant myself solidly in the middle of the room so I am surrounded, anonymous, and invisible. Sitting in the front to teach is a bit terrifying and so far, it hasn’t gotten any easier. I love being told what to do, how to move, and when to breathe, but playing the role of leader is miles out of my comfort zone. “Breathe in,” I say when I teach, and am shocked when I hear people inhale.

On the weekends, when it’s just the boys and me, I sometimes catch myself waiting for the real grownup to arrive and take over. I have moments when I feel just as I did when we took Oliver home from the birth center where he was born. “They’re trusting us with him?” I kept asking Scott, who had the same panicked look on his face.

Lately, the new responsibilities in my life are overwhelming in a way that makes me feel kind of loser-ish. A few months ago, I expressed my leadership concerns to Rolf and he told me we are at our best when we are giving one hundred percent but still feel stretched. And this is how I feel every day: stretched and still falling short.

When Scott came home from Bahrain for three weeks this Christmas, I was so tired I could barely get out of bed for the first two days. I hadn’t realized how exhausted I was, how difficult it is for me to be in charge, whether it’s in the six yoga classes I teach or at home, as the solo parent. And yet, that is precisely my role right now: to be the responsible one. To be a shepherd of sorts, ferrying my crew from one pose to the next, trusting that right action will arise for all of us.

So many of my friends glide into leadership roles seamlessly. One owns her own law firm, another her own business, and on this Marine base, I am surrounded by some of the strongest and most together women I have ever met. It’s been humbling to realize how different I am and that what comes easily to them is elusive to me.

Rolf conned convinced me to help lead his 200 hour yoga teacher training here, on Camp Lejeune, which is he offering free of charge to veterans. Most of the guys in the training also take my yoga classes, and this has raised the bar even higher for me. The 200 hour training meets once a month and Rolf dials in, appearing on the big TV screen in the yoga studio. But there in the room, I am the one in the front, the one being watched, not just in the training, but daily as I live and teach, succeeding and failing in various degrees. Like a butterfly pinned to a board, I feel exposed, and more than a little bit fragile, my own wings feeling dry and brittle.

And yet, stepping out of my comfort zone to this degree – doing what is so radically uncomfortable – has pushed me to take unusual steps. Knowing that I am being pushed in new directions has brought a new level of accountability to how I sequence my classes and to how I live. It’s so obvious to me now the areas in which I am out of alignment as a teacher, a parent, and as a person. I have had to take charge – and make changes – if not willingly, then by necessity, whether it’s encouraging my children through transitions as Scott leaves again for another five months or ushering students through a yoga class. Most of this is a two-step forward one-step back kind of thing. I feel a measure of success and then I lose patience, my sense of timing, or my nerve.

Breathe in and know you are breathing in, I say, as Rolf taught me to do. And breathe out and know you are breathing out. I am acting “as if” and hoping that some day, who I am now will catch up to who I want to be.

Stitches

June 18, 2014 § 37 Comments

“Have faith in the way things are. Love the world as your self; then you can care for all things.” – Lao Tzu

I was right in front of Oliver when he fell. I was sitting in my friend Jill’s gazebo taking a bite of watermelon at her son’s ninth birthday party as Oliver ran towards us. He and all of the boys were still in their bathing suits but had moved out of the pool and were now playing a complicated game of tag. Or maybe it was hide and seek. Oliver was running as if he was going to hide in the bushes around the gazebo, but he slipped on some dry leaves, and his face hit the wooden step. I jumped up and ran around behind him, but Jill reached out her arms and pulled Oliver up through the bushes, the gash on his face open like a second mouth. “Let me get Jon,” Jill said and handed me a beach towel.

Jill’s husband is a Navy doctor, and after what seemed like a long time, he walked over to us and calmly removed my shaking hand from the towel I was pressing into Oliver’s face. “Let me take a look at that.” After he replaced the towel he said, “Well, you can take him to the ER or I can take care of it here.” Sweat was dripping from Jon’s face. I looked down at his sneakers and realized Jill must have found him during his run.

“I want to stay here,” Oliver said.

Jill shrugged. “If it were our kid, we definitely wouldn’t go to the ER.”

Five minutes later we were sitting in their air conditioned kitchen while Jon dabbed at Oliver’s wound with Q-tips and unwrapped a package of Dermabond. “I’m going to teach you how to breathe while I do this,” Jon had said before he began, and I watched while together, he and Oliver inhaled and exhaled slowly, my own chest rising and falling, my own heart beginning to slow down.

“You’re doing great, buddy,” he told Oliver as he dripped hydrogen peroxide into the gash. “I’ve worked on Marines who yell and scream when I do this.” Oliver closed his eyes and squeezed my hand, and I had to look away and gulp air through my mouth. Last year, Jon returned from a deployment near the Helmand Province, an area rife with both insurgents and IEDs. Jon is an orthopedist, and I didn’t want to think about the injuries he saw there.

“You all made it back from Afghanistan, right?” I asked Jon after Oliver had been patched up and was proudly showing the other boys his bandage.

“The medical corps all came home,” he answered. “But not all the Marines.”

Most days, as I cut peanut butter sandwiches in half, pull weeds from the tomato beds, sit in my friend’s bright kitchen as she dumps the watermelon rinds from a birthday party into the trash, I often forget I am tied to the military, even as artillery booms across the water and helicopters fly overhead. This war has been going on for so long that I am numb to the stories, as if they belong to someone else’s life or to another world completely. And then something happens – another civil war, another battle for Falluja, another story from a friend or neighbor – and I realize that closing my eyes doesn’t mean things stop happening.

Perhaps the biggest impact of Scott living in Bahrain is that the stories I used to think were relegated to an imaginary world are now intertwined with my own. I am too aware that things I thought only existed on the news are actually happening in my lifetime, in real time.

When I do Facetime with Scott, I sometimes see the Manama skyline from his hotel, the industrial, unfinished city and the sand surrounding it. He is apartment hunting now, and in the photos he sends, I can see the Persian Gulf from a window over the kitchen island or sometimes from the bedroom. Water view, he types underneath, as if he is trying to sell me on the place.

Last week, Scott told me about a brief he had to attend about Ramadan, in which he was reminded he could not eat or drink in public and that he was required to wear long sleeves and pants. Ramadan, I think, and remember a friend who left Afghanistan in the 1980s, as a child, because her father was a Freedom Fighter. During one Ramadan right after college, I had my first chai tea in her tiny apartment while she told me about the meals her grandmother used to cook when it was time to eat again.

For so long, I have lived in small, narrow rooms, consumed by my own private joys or struggles, or simply the questions of what color pawn I want to be, when we are going to the pool, what we are having for dinner. I like being insulated like this, safe as houses. In fact, I long for a permanent home of my own with a keen and insistent wanting. I can’t wait until we can stop moving every two years like bedouin. Maybe I am even a little bit obsessed as I cut photos out of magazines, pour over Pottery Barn catalogs, and sometimes take paint swatches from Lowe’s, as if I had rooms to swath in color. So it’s probably no accident that each place I have lived has taken me further from my ideal of home, to the point where our family is no longer even together on the same continent.

My friend Christa once told me we keep getting the experiences we need until we learn the lessons, and I believe this may be true. A few months ago I read an interview by Chip Hartranft in which he defined abhyasa – traditionally translated as practice – as to sit and face what is real. When I told Rolf about this during my training, he said, “To sit and face what is real and allow it to be exactly as it is.” This may be the central lesson of my life right now: Can I keep my eyes open and let things be? Can I have faith in the way things are?

Oliver’s bandage fell off a few nights ago, which was a relief because it had gotten pretty gross. He was wearing only his pajama bottoms when he came to find me brushing my teeth, and he had to drag a step stool over to see himself in the bathroom mirror. The scar on the top of his cheekbone was small and neat, another stitch in the fabric of himself, holding together the being and the becoming. He turned from side to side, his torso lean and fragile. “You know Mommy,” he said with a big grin, “I think it looks pretty good.”

Unraveling

May 26, 2014 § 22 Comments

If I were out at sea, I’d want to know someone was waiting for me, wouldn’t you? – from “Seating Arrangements” by Maggie Shipstead

When I first read The Odyssey, in ninth grade, I thought that Penelope was a bit of a drag with her weeping and begging to be put out of her misery. I smugly thought I knew what she was doing, spending her nights unraveling the shroud she had been weaving all day in order to keep her suitors at bay. There didn’t seem to be anything more to it. The only reason I even remember the class at all is because it was where I first learned about symbolism, which felt a bit like opening a secret door.

Now, I see Penelope’s sabotaged weaving as something much different. I see the unraveling as something that happens when a person physically leaves a marriage, no matter how much love or faith remains. Until Scott left for Bahrain, I hadn’t realized how much a marriage depends on both threads, woven together in words and shared experiences and in presence. I had taken for granted the way Scott and I can look at each other and smile (or grimace) at something Oliver or Gus says, however innocuous, because it conjures up a shared, but private history. Frankly, I am surprised by this, by how I have allowed myself to become so entwined in another person’s life. For 32 years I was single, and mostly unattached. Naively, I had thought I could be in a marriage but keep my solitude and independence, that I could create a life with someone but not miss them too much if they went away.

Scott works long hours normally, and during April and May, he was gone before sunrise and often came home after dark. While I knew the weekends would be difficult, I didn’t think this deployment would make much of a change to my weeks. I had thought I was stronger than I am and I am completely caught off guard by how much I miss Scott, how much I depend on his steadiness, his sense of humor, and the ways he allows me to completely fall apart.

Now, he is living in a hotel room in Manama (it might be months before an apartment can be obtained because of security clearances) and he can Facetime with us in a computer lounge on base. He calls in the mornings or in the afternoons here, which in Bahrain, is after 10 pm. He sends beautiful emails detailing the delicious shawarma dishes he eats, the fresh fruit juices on the menu instead of cocktails, the rug shops that are open until late at night. “When you visit,” he says, “We can pick one out.” I think of those thick and colorful tapestries, and I feel myself coming undone.

Scott told me that the international school where we would have sent the boys is on the edge of a Shia village, or a black zone, forbidden to Americans because of sectarian violence. He told me about the big fence around the school and the graffiti on the walls, the armed guards who ride on the school buses. On one of his first nights there, the street with American restaurants was closed because protesters were burning tires. Scott also sent beautiful photos of the Manama skyline sparkling at night, of the tan and empty desert, and the twin spires of the Grand Mosque, which my mother accurately pointed out, “look so much more interesting and exotic when they are in your own email box instead of in a magazine.” When I talk to him, I can almost feel the heat he describes or smell the bahji puri, but mostly, I just feel so far away.

My neighbor’s husband is in Guantanamo Bay for nine months, and the other day, while she was walking her dog, she warned me the weekends are the worst, and this holiday weekend proved her right. Oliver has been extremely difficult lately, both needy and angry, and I am trying to be understanding while also holding the line that must be held for him. Of course, I am flooded with doubt over every decision. Oliver loves boundaries even as he rails against them, making faces at me, talking back, telling me he doesn’t care that he has lost his screen time. In a single day, I am both the meanest mom on the planet and the best mom in the world.

Today, we drove 90 minutes to Wilmington, mostly because I couldn’t stand the sight of one more father firing up a grill and because I was feeling angry and needy myself. We went to a historical, working plantation and then to a children’s museum. “I know you’re having a hard time,” I told Oliver, after I made him sit down because he wouldn’t leave his brother alone. He looked at me with his father’s eyes and said, “It feels like a piece of my heart fell down into my stomach.”

Jason Crandell, the yoga teacher, recently posted this on Facebook: “Your edge is the threshold in a pose—or moment in seated meditation—where physical, mental, and emotional resistance comes rushing to the foreground. Reaching your edge is like applying an enzyme that ignites a reaction and magnifies your physical, mental and emotional patterns.”

This leaving has revealed a jagged edge I didn’t even know was there. I didn’t realize my husband’s journey across an ocean would dredge up all the other times I had been left, and even worse, the magnification of all the ways I abandon myself. I hadn’t known this fact about myself, which is that my constant doing might become my own undoing, that I don’t really know how to stop, how to be still, how to let go. I know how to fill a space with yoga or reading or meditation or watching TV, but this is wildly different from doing nothing or becoming empty.

For the first few nights Scott was gone, I didn’t really sleep. As another dawn began to leak through the night, I felt as though vines were wrapping themselves tighter and tighter around my chest. Already, I was thinking of cleaning the house, going on another cleanse, doing a 40-day meditation sadhana. I know how to tighten and how to restrict. I know how to take away and how to cleave at the messiness until I am clean and sharp. But as I lay there, listening to the buzzing satin of the dawn, it became clear that while I know how to fall apart, I have no idea how to unravel.

Images have been in my mind and heart lately: kelp fronds waving in cold oceans, wind chimes untwisting in the wind, the line from the Tao te Ching that reminds me to have faith in the way things are. I don’t yet have enough faith to believe that everything happens for a reason. There is too much darkness in the world for me to believe in both this and a benevolent god. But I have a sense that in my own good life, I am getting lessons I need to learn. Today, in the plantation, we peered into a weaving studio with a spinning wheel and a loom. Outside, sheep grazed and inside the wool was carded. Fabric was woven together and dyed and sewn into something that can be worn. And yet, I was focused on the undoing of it all, the unweaving, and the unraveling, and what it might feel like, when I too learn how to twist and untwist in the wind.

Sankalpa

January 2, 2014 § 18 Comments

I always wonder what the world would be like if we all had the same intention, to focus more on love. I don’t know. It could be very awesome. – Britt Skrabanek

Ever since I was in college, I have gotten sick in November. In college, the day after cross-country season ended, I would come down with a sore throat, a cough, a stuffed nose. Last year, I had bronchitis. This year was mild. I caught a cold and lost my voice after I taught several yoga classes. For a week, I could only whisper. I could no longer yell upstairs to the boys to brush their teeth or stop fighting or to come down for dinner. Instead, I had to walk up the stairs and pantomime holding a fork up to my mouth or point to my throat and shrug. Most of the time, the boys acquiesced and came down to dinner or resolved their arguments, usually upon Oliver’s lead.

I felt extraordinarily calm all week, which is rare for me. At the bus stop, I just stood with the boys and waved to the other mothers. When Gus came home from school, we played Uno or we went down to the bay across the street and found driftwood and shells, secret trails to the water, and animal footprints. During the evening, I walked out the back door and watched the sun as it fell into the water, leaving a wake of purple and grey and orange. Because I didn’t feel terrific, I went to bed early, and the time on my meditation cushion was easier, less fraught with all I wished I hadn’t said. The week of the lost voice made me see how rarely I needed to speak, how much of what I usually say is just an extension of the chatter in my mind.

After several days, a haggard whisper came back and then a croak. The next Monday, after Gus came home from preschool, we were in his room putting away laundry and Legos. “Mommy,” he said, when I asked him to hand me some socks, “I am going to miss your lost voice when it’s back.”

“What?” I asked, “Why?”

“Well,” he said, “It’s just that you’re loud. You talk in a loud voice.”

When I told Scott he laughed. “You are loud,” he said. “I worry you don’t hear very well.”

After my voice came back, it was Thanksgiving, and then Christmas came after like a freight train. Oliver broke his leg and was miserable of course, his cast edging up to his thigh. He was unable to ride his bike or play soccer, and he and Gus began bickering in the afternoons. The holidays grabbed me around the ankles and tugged. There was so much to do, from Scott’s work parties to buying presents to spending 22 hours in the car driving to Pennsylvania and back.

This year, the holidays were loud.

On a Friday, right before the Solstice, I took Gus down to the water across the street at sunset, while Oliver stayed home with his crutches and a book. “Look Mommy,” Gus said and pointed to the sky, which was molten and darkening quickly. “It’s the wishing star.” We stood there, side by side, listening to the rat-a-tat-tat of artillery practice across the bay. A great blue heron flew out of a tree, stretched its wings over our heads, and echoed the staccato of gunfire with its own prehistoric squawk. For a moment, I felt as if there was no time, that it had ceased to exist or maybe just collapsed, all time layering itself upon itself, wringing out the important moments and ending up with a sunset.

After Christmas, I went through the usual foreboding prospect of choosing A Resolution. The lapsed Catholic in me still approaches events like this as if they were a kind of penance: a whipping strap with the hope of salvation attached. And then I read Britt’s blog about creating a Sankalpa instead. A Sankalpa is both an affirmation of our true spirit and a desire to remove the brambles which can prevent us from manifesting that deepest self. It is a nod to the fact that we are in a process of both being and becoming, it’s a rule to be followed before all other rules, a vow to adhere to our heart’s desire.

My heart’s desire is for more quiet. More sunsets. More silence. More conversations that mean something, that both press on the wound and ease the ache. More jokes and more laughter. More saying yes when I mean yes and no when I mean no. More eating sitting down. More walks on the beach, hunting for sea glass. More reading and more sleep.

When I think about it, my inability to be quiet is really an inability to be in a moment exactly as it is, to be with myself exactly how I am, to not shake my feelings around as if I am panning for gold, looking only for the good rocks, the ones that shine. Instead, my Sankalpa is to be quiet, to place the strainer down and plunge my hands into the cold and dusty water.

If you would like to continue the Sankalpa Britt suggested, I would love to hear about it in the comments.

Happy New Year!

Choice

October 28, 2013 § 40 Comments

“Apprentice yourself to yourself, welcome back all you sent away.” – David Whyte

I am approaching this space with chagrin, a sense of hands wringing in the space at my center. In August, I vowed I would write here more, and once again I have broken my word, those promises I make to myself that are more fragile than they should be.

In the spirit of true disclosure, September and October have been a bit of a boondoggle around here, and when things get tough, I tend to hide. Or, I tend to make myself so busy that I have no time to sit still, or to think, or to begin the clumsy and tedious process of sorting through words, picking them up and throwing them back as if they were tiles in a box of Scrabble.

I love the month of October, but it has an edge to it for me now as it is the month when we begin to get a hint of our next orders – Scott’s next assignment – the place to which we will be moving next. Every odd year in October, I get a whiff of endings as the leaves fall down and I need to prepare myself for the leaving and then, for the arriving. This year, I was relaxed about it and far too confident. We had thought this would be the move where we prioritized where we wanted to live rather than the right career move. This was going to be a move for family and not solely for the job, and I was excited about the liklihood of us moving to either The Netherlands or back to California, which is the place where I feel most at home.

So, it was a bit of a sucker punch that the Navy came back with two options, each requiring Scott to deploy for a year. He will choose between Bahrain and Djibouti and then the Navy will send him to one or the other, regardless of his choice. “Jabooty?” I said to Scott when he called me from work. “I don’t even know where that is.” It sounded like the punch line to an old Eddie Murphy joke.

“It’s in Africa,” he said, “Near Somalia,” and I said what the hell.

For the last month or so I have been wondering how on earth I will parent our two boys alone and how I will shore us all up enough to get through a year without Scott, whom we all adore and lean on to a ridiculous extent.

Right now, I can’t imagine it.

Two weeks ago I went to open the fridge in the garage and had a strange sensation of being watched. I glanced up and saw the beady eyes of a tree snake, its body wound around the freezer door. I ran back into the house calling, “Scott! Scott you need to come out here now!!!”

Last Friday, I discovered there was a mouse living in the seats of my car and I almost had a heart attack. I called Scott who was on his way to give a speech and cared not a wit about the fact that rodents were living in my car, so I texted the strongest and most stalwart of my neighbors. “I’ll be right over,” Tammy texted back, and together we tore apart my Prius and found that my emergency granola bar stash in the trunk had been raided, the wrappers shredded and stuffed into the interior of the back seat.

My other neighbor across the street, Miriam, drove by on her way home and leaned out the window of her minivan. “What are you guys doing?” she asked. When we told her, she parked in her driveway and walked over with her four-year old daughter and her yellow lab. “If it were me, I would get a new car,” she told me and I explained that getting a new car would require driving this one someplace first, and I wasn’t about to get in.

“Really?” Miriam asked. “But you’re so brave.”

“What gave you that idea?” I asked, and she shrugged. “I don’t know. You had a snake in your garage. Or maybe it’s because you have boys.”

“No,” said Tammy, who has a daughter and a son. “Boys are easier.”

And so the conversation turned again to the every day ordinary, as it always does, and Gus circled around us on his bike. We were gathering up the shredded paper and my reusable grocery bags, now ruined with mouse droppings, and I felt a tide of panic begin to ebb in. I am used to this now, the anxiety that seeps and slides until it rises up to my throat. “How on earth am I going to get through a year on my own?” I asked the women next to me and instantly felt silly because these women were Marine wives. Scott was gone for 8 week intervals during the first two years of our marriage, but these women have already been through more than five deployments each, their husbands away more often than they are home.

“You’ll call us,” Tammy said matter of factly as she slammed my trunk shut, and I felt something sink down and land.

“Yes, you’ll call us and you’ll get a dog,” said Miriam and then told me about the time a raccoon jumped out of the garbage can at her while her husband was gone. “If you’ve ever wondered why I take my trash out at noon, now you know.”

Gus once again circled our piles of seat fluff, and then the school bus pulled up and all of our children spilled out. Oliver and Gus got on their scooters and rode over to their friends across the street and Miriam’s girls were excited to add another “nature story” to the newsletter they are creating for the neighborhood, entitled The Saint Mary Post. “Mrs. Cloyd,” Miriam’s oldest said breathlessly as she pulled a notebook out of her backpack. “What was your reaction when you discovered mice were living in your car?”

What is my reaction to anything? I thought to myself. Out loud, I said, “EEEEEEEEEK!” which Laura Fern wrote down, her pencil pressing hard into the paper.

I’ve started running again after a slew of injuries, but I suppose it’s more accurate to say that I jog slowly for a few miles. The other morning, after the boys got on the bus and the tide of panic was rising up my ribcage, I laced up my shoes and set out. I thought about my reactions, how usually they are negative, because most of the time I am afraid. Most of the time, I am the opposite of brave. On that morning jog I was angry about the deployment, angry because this was supposed to be the move where I got to choose. This was supposed to be my turn. Mine. Not the Navy’s.

Well then, said a small voice inside me, Choose this.

“No,” I said back, but then I felt that softening again, the landing and I wondered if I was allowed to choose something I didn’t want, if it was even possible, if maybe, choosing has nothing at all to do with wanting. I don’t want a mouse in my car or my husband to leave. I want what I want and inside me, wanting has always been fierce, its claws always pulling me away and out and up. Look at this, wanting says, racing up to me on scurrying feet. Isn’t it lovely?

And now I am trying to put the wanting aside, which is something new for me. Shh, I am telling it, Not now. I use soothing words like hush and sometimes a firm word like stop. I am practicing.

Yesterday I had to teach yoga, which requires me to drive. I went out and stood in front of my car. I opened the door and removed the empty mouse traps Scott had set the night before, but their emptiness proved nothing to me. “I think it’s gone,” Scott had said as he looked under and around the seats, but I wasn’t buying it. You never know when those feet will scrabble up your spine, when those sharp teeth will sink in, grabbing your attention away and out and up.

I got in the car and fastened the seat belt. “Hello mice,” I said into the meaningless quiet and then I got the willies just thinking about them. I wanted a new car. I wanted another option. I wanted things to be different.

And then to myself I said, Shh. Not now. Drive the car.

I am still practicing.

Atonement

September 18, 2013 § 19 Comments

Yom Kippur: Going into the innermost room, the one we fear entering, where fire and water coexist like the elemental forces in the highest heavens our ancestors, the ancients, observed in awe. – Jena Strong

Last week was Yom Kippur, which is a holiday I love even though I am not Jewish. My parents are Catholic – my mom the only one practicing – but growing up, we were invited to enough Passover Seders that hearing the words: Baruch atah Adonai elohaynu melech ha’olam instantly reminds me of spring. I don’t celebrate Yom Kippur but I wish I did. We should all have a day to look inside, to take stock and be quiet with what we find.

As a Catholic, I went to confession. I always hated confession, the way I had to pull that velvet curtain back, kneel down and tell the priest my sins. I lived in a small town and it was a pretty good bet he could recognize my voice. Bless me father for I have sinned, I always began, and he usually gave me an Our Father and three Hail Marys to say for penance, which I did after I left the vestibule. This time, I would kneel in relief, bowing in the bright light that filtered through the stained glass windows of the church.

In the chakra system, the element of atonement is in our throat, where we express our ability to choose – what we say yes to and what we say no to. Do we choose our own will or a divine will? The fifth chakra is a yogic version of Yom Kippur, or as Caroline Myss so beautifully describes it, a place where “we call our spirits back.”

Two weeks ago, I got into the car after a yoga class I taught at the fitness center on base. I truly love teaching on base even though we practice on the gritty floor of a cold, group exercise room. Before class, I turn off the flourescent lights and the fan, the strobe lights that are usually still flashing from the Zumba class that ends right before my own. I place 12 battery-operated candles at the front of the now-dark room and unroll my mat. I plug my iphone into the stereo and play Donna DeLory or Girish – music that does nothing to tamp down the blare of Taylor Swift from the gym or of the sound of weights being racked right outside the door. I love teaching in that gym, which smells like an old boxing ring and is always jam packed with Marines. My Tuesday yoga class is usually full due to prime scheduling time, and I leave there feeling buoyed up and overflowing.

That Tuesday, two weeks ago, I sent a text to my babysitter from the gym and then got in the car and headed home. For some reason – maybe because I felt particularly immune that day or maybe because the boys weren’t in the car – I hit the redial button on my phone and put it on speaker. Scott had ridden his bike to work that morning because his car battery died, and I thought I would be charitable for a change and see if he needed me to bring him anything. I picked up the phone and said hello and 30 seconds later a police car was behind me, his lights flashing. I pulled over, instantly beginning to tremble. Oh my God. Oh my God. Ohmygod. A few months ago, one of Scott’s guys had gotten pulled over for talking on his phone while driving and he lost his driving privileges on base for 30 days. I couldn’t lose my driving privileges. How would I take Oliver to soccer? How would I get to the grocery store? How would I teach yoga? Losing driving privileges on base is pretty much like house arrest.

I watched in my side mirror as the Marine police officer got out of his car and ambled over to me, pushing his sunglasses onto the top of his head.

“Ma’am,” the officer said, and nodded at me through my open window. “Do you know why I pulled you over?”

“Because I was speeding?” I asked hopefully.

“I’m afraid not,” he said and then asked for my driver’s license and registration. With trembling hands, I handed him my credit card. “Ma’am?” he asked again, and I fumbled for my license. I gave it to him and he held it up for a second. “You were using your cell phone without a hands-free device and that’s illegal on board Camp Lejeune.” I watched the muscles in his forearm twitch. He couldn’t have been older than 25, and he looked as though he could crush my Prius with his bare hands.

And then I did it. “I wasn’t talking on my phone,” I lied, my heart racing, thinking about what it would be like to not be able to drive for 30 days, to be stuck way out at the end of Camp Lejeune. “I was plugging it into my stereo system.”

I looked over at the passenger seat where my yoga mat rode shot gun next to the blankets and blocks I bring for the pregnant woman who comes to class. The lie sat there like a hairball.

The officer nodded graciously. “Maybe that’s the case Ma’am,” he said. “I saw you holding your phone up and your lips were moving, but maybe you were singing along to the music.”

I closed my eyes and felt my face get hot.

“This won’t affect your driving record,” he said kindly. “But you will have to go to traffic court. The judge will decide if you’ll lose driving privileges or not.” He gave me a tight smile. “Your record is pretty clean, so my guess is not.”

He let me go with a pink slip of paper and a number to call and I drove home, feeling shame rise up to my scalp. Who was I?

That afternoon I called Scott in tears and I texted two friends who told me everyone lies, that it wasn’t a big deal, but it didn’t make me feel any better. The next day on the way out to the bus stop, my neighbor across the street called out, “Hey, you made the police blotter!” She seemed to think this was hilarious. My next-door neighbor’s husband was there too and he laughed.”You’ll be fine,” he assured me. “I know the magistrate at traffic court and he’s a nice guy.” The truth was, I didn’t really care about traffic court anymore or even about losing my driving privileges.

Last year, right after Christmas, I was practicing handstand against my bedroom wall before I went to teach a yoga class. Because I have been working on balancing in handstand for the last four years, this is not usually a problem for me. But for some reason, on this night, I totally freaked out once my hips were off the ground. Ohmygod, I thought and my legs began to flail before my foot banged on the dresser and my knee crashed into the floor. It hurt so much that I could only curl into a ball on the floor and try not to throw up. My pinky toe was black for a week and my knee still hurts if I put too much weight on it.

After leaving the bus stop that day – my neighbors calling our reassuringly that it would be OK and don’t worry – I thought about that handstand. That’s who I am, I thought. I am someone who completely loses her shit when her back’s against the wall.

On Monday, after I heard about the shooting at the Navy Yard, I texted and emailed some friends. My former roommate told me that her husband was OK but that he had been on the fourth floor and barely made it out. He spent a few hours that morning in lockdown with a woman who had collided with the shooter. She begged the shooter not to kill her, my friend wrote to me, and for some reason he spared her life. I thought about Scott, who was at the Navy Yard several times a month when we lived in DC. Even I had been there a couple of times to meet with a lawyer to finalize our will. It’s only a few blocks from the Metro stop on M Street, close to the ballpark, smack dab in the middle of the city.

For most of the day Monday, I tried to find a reason for the tragedy, for something to reassure me that we don’t live in world where survival is a total crap shot. But guess what about that.

On Monday night I had to teach yoga at 6:30 and I pretty much had nothing except an essay from David Whyte called “Ground.” Yesterday – a Tuesday – I drove to the fitness center after the bus left. I lugged my bag of candles into the cold group exercise room and turned off the lights. Because I am a mostly selfish person, I decided to focus the class around our throat chakra. When everyone was lying still on their mats, I told them about my day on Monday, about how my own attempt to find reasons for the senselessness of the tragedy at the Navy Yard looked a lot like blame: If only they had checked the trunk of his car. If only we had better gun laws. If only.

I also told them something I believe is true, which is that we are all connected. That the only way to change the world is to change ourselves. If we want more kindness in the world, we need to be more kind to ourselves. If we want there to be less judgement in the world, we need to stop being so hard on ourselves. Thoughout the class, we opened our throats and softened our jaws. We did side plank and arm balances, followed by child’s pose. “Notice if you are judging yourself or comparing yourself to someone else,” I said to them, but really to myself. “And if you are, then simply call your spirit back.”

I was shaky and a bit off in class. When I was assisting a student in Warrior III, we both stumbled. I kept thinking about the woman whose life was spared. I kept thinking about my lie. I kept thinking about how connected we all are, that there are no bad guys and no good guys. There is only us.

Last night, a chill slid into the air. September, which has been clunking along so far with its heat and its bad news seems to be slanting towards fall after all. Under the full moon, I watched a few leaves blow around in a circle and I thought of Macbeth. Let not light see my black and deep desires. And yet, it’s the light that matters. And for some reason, he spared her life.

Today, I had to report at traffic court at 7 AM. I had to stand in front of a judge with my pink slip and tell the truth. “How do you plead?” he asked me and I said Guilty. But it doesn’t really matter about traffic court or even the judge. In the end, there is only us.

Ground – David Whyte

Ground is what lies beneath our feet. It is the place where we already stand; a state of recognition, the place or the circumstances to which we belong whether we wish to or not. It is what holds and supports us, but also what we do not want to be true; it is what challenges us, physically or psychologically, irrespective of our abstract needs. It is the living, underlying foundation that tells us what we are, where we are, what season we are in and what, no matter what we wish in the abstract, is about to happen in our body, in the world or in the conversation between the two. To come to ground is to find a home in circumstances and to face the truth, no matter how difficult that truth may be; to come to ground is to begin the courageous conversation, to step into difficulty and by taking that first step, begin the movement through all difficulties at the same time, to find the support and foundation that has been beneath our feet all along, a place to step onto, a place on which to stand and a place from which to step.

GROUND taken from the upcoming reader’s circle essay series. ©2013: David Whyte.

I Want to Remember

September 26, 2012 § 16 Comments

I was inspired by Lindsey Mead Russell’s writing prompt “I Want to Remember” who was inspired by Ali Edward’s. To read Katrina Kenison’s, click here.

I want to remember the way the butterflies here careen towards my head in their ridiculous flight and make me duck, every time. I want to remember my next-door neighbor, the way he came striding over to me in his camouflage and combat boots, the sun high and his shadow arriving first. “I’m Bobby,” he said, just as I was wondering whether to advance or retreat. “Let me know if we can do anything for you while you’re getting settled, anything at all.” The next day, the woman across the street walked over in the rain with a plate of cookies and her phone number and I felt something settle, despite the boxes we had yet to unpack.

I want to remember the way I feel in the morning, how in the half-second after my alarm goes off, I am still not sure where I am. I want to remember how much I despise yoga at five in the morning and how very much I need to throw down my mat, to hear the particular sound it makes on the wood floors when the house is dark.

I want to remember these days, when my insides feel full of the sharp click of needles. I stare down the street at the identical houses and realize I am both tourist and native. The morning after we moved in, I waited for the school bus with Oliver for the first time, feeling such camaraderie with the other mothers. After the bus drove off, one of them told me her husband had been to Iraq and Afghanistan five times, once for fourteen months. I went back into the house after that, into a different sort of day.

I want to remember the sharp taste of the ocean, the bitter reminder of a war, a heat so impressive that it sometimes feels as though I have landed on the tongue of a dragon.

I want to remember what it was like to run through the cornfield behind my house when I was nine, my hands slapping hard at the leaves. I want to remember leaning over the withers of the pony I leased every summer, the moment when she gathered herself up and then exploded into a gallop. Her exquisite speed made my eyes useless until finally I closed them and wound my fingers through her mane.

I want to remember what artillery practice sounds like on Camp Lejeune, the air imploding on itself and the windows rattling as if in an earthquake or a battle. I want to remember the way my new friend folded herself onto the floor of our house, the walls still smelling of paint. She talked about her autistic son, each detail a gift, beads carefully strung. I want to remember what she quietly called testimony, the way she turned her face briefly towards the ceiling and said that her son gave her faith, that he caused her to believe in God and trust in this life.

I want to remember the man with nine fingers who came to fix the air conditioner, whose Carolina accent sounded like a banjo playing in the night. He asked me if I was from Mississippi and when I shook my head he told me, like a prophesy, that I was going to learn to cook black-eyed peas. I want to remember the way he talked about getting injured in the first Desert Storm and how he alternatively called me Ma’am and Sugar. Shuguh.

I want to remember the soldiers in the field next to the post office and how they were taking turns carrying each other over their shoulders, wrists and ankles dangling towards the ground. I want to remember the way Oliver runs with his arms outstretched, pretending he’s a falcon and the way Gus throws his head back and laughs when anyone says the word “stinky.” I want to remember Oliver racing off on his bike, sometimes tossing his legs over his handlebars and how Gus rides away from me, his back straight, one training wheel perpetually off the ground.

I want to remember my college teammate tell me at breakfast one morning what it was like to live in Bosnia in 1992, how her mother made her sneak up the street and check for snipers before she went to school. I want to remember the camping trip to Mexico my second year out of college, how my friend calmly described what it was like to flee the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan and travel to Turkey under the cover of night.

I want to remember my new yoga teacher reading from Meditations from the Mat, and how relieved I was to hear something so dear and familiar to me I wanted to cry, hunched over in child’s pose, my forehead pressed against the ground.

I want to remember every bit of how uncomfortable I am here because I am not someone who does uncomfortable well. I am someone who runs like hell from uncomfortable, who would rather turn away than look at the woman in front of me with the baby and the food stamps. I am not here to give testimony to a god but instead, to the way the world crouches between beauty and despair, each a tragic partner to the other. I can only bear witness to those dark and fragile moments before dawn, when it looks as though things could go either way.

Freedom

September 10, 2012 § 16 Comments

“Sometimes life hands us gift-wrapped shit. And we’re like, “This isn’t a gift, it’s shit. Screw you.” – Augusten Burroughs

“Well Jacksonville’s a city with a hopeless streetlight.” – Ryan Adams

This has been a very difficult summer for me for reasons that have more to do with my own mind and less to do with what actually happened to me. When we moved from Washington, DC to Jacksonville, North Carolina, we knew we would have to wait at least six weeks until a house was available for us on the Marine base here. I just didn’t think that at least six weeks would actually stretch out until fourteen weeks, longer than a Southern summer, all of us sleeping in one room from Memorial Day until weeks past Labor Day.

I am trying to realize how lucky I am to have the privilege of staying in a hotel for this long, and if you could see this town, you would understand. It’s the kind of place where a steady stream of women and children file into the WIC office, and the Division of Employment Security always has a few men sitting on the curb outside, their arms wrapped around their knees. Driving from our hotel to the base, where Oliver just started first grade, we pass countless pawn shops and tattoo parlors, a Walmart, a Hooters and a windowless, cinderblock “gentlemen’s” club called The Driftwood. Before I arrived in Jacksonville, I didn’t believe places like this existed outside of New Mexico or movies starring Michelle Williams. I recently discovered that one of my favorite musicians – Ryan Adams – grew up here, and as I again listen to him crooning those heartbreaking lyrics, I am not surprised. Jacksonville, North Carolina may be the saddest, hottest, dirtiest town I have ever set foot in.

In early August, one of the housekeeping staff stopped me on the way down the hall. She held out her palm and asked me if the small, brass, semi-automatic bullet in her hand was mine. “Um, excuse me?” I asked, feeling my jaw drop open and then I shook my head. “No,” I said, “No, we don’t have a gun.” Jesus, I thought as I walked away and then I turned around. “Where did you find it?” I asked and the woman told me that it was right behind the bed where my sons have been sleeping.

Later that month, I took the boys to the indoor pool one afternoon. We did this a lot as Scott was traveling for a couple of weeks and it rained every day he was gone, the sodden hem of Hurricane Issac dripping over Jacksonville. On that grey day, Gus jumped into the pool, into my arms, before I was ready and his head banged into my eye. “You’re bleeding!” said another woman in the pool so we all got out. By the time we were back in our room, I could feel my eye swelling. The next day – Oliver’s first day of school – there was no amount of concealer that could cover the purple and green lump under my eye and the gash right above it. I met Oliver’s teacher noticing her eyes flickering with concern as they focused on my shiner, knowing that there was nothing I could say that wouldn’t sound as if I was making an excuse for something. I told Scott it was a good thing he was out of town.

I’m not who you think I am, I wanted to scream, which has been sort of a mantra of mine all summer, mostly to myself. Since June, I have been trying to convince myself that I am not homeless or a failure or a lousy mother but it’s been challenging as I keep finding myself in situations where it’s easy for people to take one look at me and get the wrong idea. All of my life, I have been an incredibly judgemental person, and this summer, my judgements were turned inward, towards myself. Or maybe that’s where they’ve been all along.

I never thought I would become a military wife. I was born in the early 70’s, in the heyday of Women’s Lib, and as a teenager, I swore I would never let myself be defined by a man. A military wife was pretty much the last thing I imagined, and there is a small part of met that feels like I let someone down. This summer a bigger part feels like I’ve let my kids down, tearing them from their friends in Washington, DC and our big house there and sticking them in a single room with a bag of Legos each. Oliver, especially, has had a tough transition from his Waldorf school to his Department of Defense school, where already, he is expected to keep a journal. Tonight he had to write a paragraph about what freedom means to him.

Freedom. In Jacksonville, the word “Freedom” is everywhere: on teeshirts and bumper stickers and even on the sign welcoming you to Camp Lejeune. “Pardon Our Noise,” it reads, “It’s the Sound of Freedom.”

In yoga, freedom means to be released from the chains of our mind, and this summer, living in a tiny box, I have seen how chained I am to my own idea of how things should be, how chained I am to my ideas of how other people should be, to how I should be. What is true is that I have exactly what I want: I married my best friend, a man I am still madly in love with after a decade of being together, and I am able to stay at home with my kids, which I am lucky to be able to do. Scott supports my yoga habit, stayed home from work one day a month last year so I could go to my yoga teacher training, and he doesn’t complain about eating kale or Gardein Chik’n, which I have been making often in our hotel.

What is also true is that getting what I wanted doesn’t look the way I thought it would, and I get upset about that, some strange combination of guilt at not having a job and resentment that I have to follow someone else’s orders and traipse after a man. Every other place we have lived – San Diego, Ventura, Washington, DC, Philadelphia – I was able to pretend that I wasn’t a Navy wife, that I had nothing at all to do with the war waging in a far away desert.

In Jacksonville, I can’t hide anymore. The town is crawling with soldiers. You can’t turn your head without seeing a Semper Fi bumper sticker or a Marine Wife window decal, a gaggle of young recruits sauntering down Western Boulevard, or a young man in a wheelchair, empty space where his leg used to be. Something about this town has brought me to the bottom of myself, to the place I have been avoiding for years, covering up with power yoga and running, volunteering and a second glass of wine.

And yet, there is a relief in the crumbling of an unstable structure because once the last wall falls, you find yourself sitting in the middle of a dusty, empty space that feels a bit like what freedom might feel like if freedom didn’t stand for guns or bombs or a country’s foreign agenda. Once you find yourself on rock bottom, there is nowhere left to go. You have already eaten the cupcakes and run the miles and held Warrior II for days and nothing has worked. Nothing has changed except the myriad ways you have thrown yourself against the walls. And then, one day, after cursing the sun that beats down upon the ruins, you finally sit up and survey the jagged thoughts shredding your heart. You say, “Well then. This must be the place.”

Jacksonville is that place. Our stale and musty hotel room is that place. Oliver’s new-school anxiety is that place as is my acquired and inherited shame that I will never be good enough. In his yoga DVD, Baron Baptiste says, “That which blocks the path is the path.” This summer, I have been punched in the face with my own resistance, with my tight-fisted grip on the way I think things should be. I have been handed bullets and black eyes and I keep forgetting that these are the gifts. I forget that the lessons are handed out in the trenches, in the foxholes, in the dust of crumbling temples. I am discovering that wisdom hides in the most wretched of places, buried deep in the towns with the hopeless streetlights.

Click here to hear Ryan Adams sing about his hometown, Jacksonville, North Carolina.

Lumps

July 2, 2012 § 11 Comments

Too often we give away our power. We overreact. We judge. We critique. And we forget to breathe. – Seane Corn

In mid-June, Scott’s parents flew in from Oregon and my own parents drove down from Pennsylvania to visit us here, in North Carolina and to attend Scott’s change of command ceremony on Camp Lejeune. Because I couldn’t possibly imagine our families in this strange extended-stay hotel with us, we rented a house on Topsail Island for a week. It was such a relief to be able to open a door and let the boys run outside, to sit on the beach without driving there, to walk near the warm waves at night and wake up and do yoga on the deck outside our bedroom.

And then it was time to leave. My little blue Prius was so full of suitcases and sand toys, cardboard boxes full of peanut butter and oatmeal, raisins and spirulina powder, a pint of berries and an eight-dollar jar of red onion confit I bought at Dean and Deluca in Georgetown before we moved because I had to have it. The boys could barely fit into their car seats, and on the passenger seat next to me was a laundry basket full of bathing suits, my Vita-Mix blender, a Zojirushi rice cooker, and a Mason jar full of the seashells we found on the beach.

It was a little after eleven in the morning. It was past the time we were supposed to be out of the beach house and hours until we could check into our hotel. We had already spent the morning on the beach, and as I steered the heavy car out of the driveway, I realized I had nowhere to go.

You’re homeless, you know, said The Voice inside my head. You are 39 years old and you have no place to live.

I am not, said the Other Voice. I am not homeless.

And yet, you have no home, said the Voice, So what would you call that?

We spent some time at the Sneads Ferry library and checked out some Magic Treehouse books on tape to listen to in the car. We drove to a park with a big boat launch in Surf City and boys watched with fascination as pickup trucks hauling fishing boats expertly backed up to the water and set their boats free. We watched a big blue crab walk sideways in the brackish water and the boys threw leaves at the tiny fish that shimmied near the docks. We went to a pizza place for lunch because I knew there were clean bathrooms there and we went back to the beach where the boys were cranky and kept grabbing each other’s shovels.

The night before, when we were still in the beach house, I felt a lump on the side of Gus’ neck and my heart leapt up into my throat. I asked my father-in-law to take a look and he told me it was nothing. “Don’t waste a doctor’s time with that old thing,” he said, which comforted me greatly, but still, while the boys stole each other’s beach toys on that homeless day, I was on the phone with a pediatrician’s office. “Why don’t you come in tomorrow?” the receptionist asked me and I felt my unreliable heart writhe and squirm again.

I gave the receptionist my name and my insurance information. She asked for my address just as Gus hit Oliver on the head. We had gotten a PO box the week before, but I hadn’t memorized it yet, and it was clear that if I didn’t get off the phone, one of the boys would hit the other with a plastic dump truck or the bright yellow buckets I bought a few days earlier. “I don’t have it right now,” I told the receptionist. “We just moved here. Can I bring it tomorrow?”

The next day, we arrived early for Gus’ appointment. The waiting room was nearly empty and as I was filling out form after form, a nurse came out and stood by the receptionist. “She didn’t have her address yesterday, so I couldn’t start the file,” I heard the receptionist say in a loud whisper. “Honestly who doesn’t have an address? Who are these people?”

I felt tears start in my eyes and my whole face ached with shame and fury and a feeling of desperation so great that I wanted to jump in my car and watch the entire state of North Carolina recede in my rear view mirror. Hey, I wanted to say, I can hear you. Instead I said, “I’m almost finished,” and watched the receptionist jump and turn around. I walked up to her desk with my completed forms but couldn’t look at her, my face hot with the shame of having no address, no place to go, no home.

Afterwards, when the doctor told me I had nothing to worry about, that the lump was just a swollen lymph node, I was so relieved I took the boys for ice cream. The main road into Jacksonville – Western Boulevard – is particularly ugly, but the week before, on a walk, I found a little ice cream place called Sweet, which looked brand new and cozy. It was sandwiched between a Five Guys and a Popeye’s, but inside Sweet were velvet couches and soft chairs, a coffee bar and an old-fashioned ice cream counter. A sign on the wall announced that there would be a benefit tomorrow and NFL MVP Mark Moseley would be signing autographs and footballs.

The boys and I sat on a couch and ate our cones and a few seconds later, an older man sat down in a chair next to us with a coffee. His white hair was slicked back and he was wearing a black button-down shirt, black jeans, and a belt with an enormous buckle. On his right hand was a garish gold ring and on his feet were the most amazing pair of cowboy boots I had ever seen. The brown leather rippled in shades of light caramel and gold and deep chocolate. My first thought was to sneer at his outfit. Where do you think you are, Texas? asked The Voice, and then I thought of the receptionist we just left and was flooded with a new shame.

I wanted to be nothing like that receptionist, nothing at all like her, so I looked at the man and said, “Those are some really nice boots.”

The man stretched out his legs and lifted the toe of one boot into the air. “Thanks,” he said. “They’re gator skin. I have four pairs.”

“Four pairs?” I asked, delighted, as I always am when someone has exactly what they want, when they unabashedly showcase more than I think any of us are allowed to have.

He nodded at me and I tried to imagine four pairs of those boots lined up in my bedroom closet. In my head I thought of the tiny wooden closet in our old Virginia house and once again, I remembered I was homeless.

“So how do you like our ice cream?” the man asked me and I nodded and then said, “Oh so this is your place?” because sometimes it takes me a while.

The man nodded again and I watched the sunlight flash on his tacky ring. “I own the Five Guys and the Popeye’s and I wanted to bring in something different,”he said.

I told the man that my friend owns a Five Guys at the ballpark in DC and the man said, “Charlie? I know Charlie. Are you from DC?”

I said that I was, that we just moved here. “Your husband on the base?” he asked and I told him that Scott was a Seabee, that he was part of the huge construction project on Camp Lejeune. “I met with some Seabees last week,” he said. “I’m trying to get Five Guys on the base.” He asked me more about Scott’s job and then we talked about DC for a while. Oliver asked if he could have the rest of my melting ice cream come and I gave it to him. “I lived in DC for fourteen years,” the man said, “I was the kicker for the Redskins. It’s a great city.”

“The Washington Redskins?” I asked, as if there were any other kind. I am not a football fan, but my father and brother are and I grew up around detailed conversations about Joe Namath and O.J. Simpson, Refrigerator Perry and Mean Joe Green. When I think of those long ago Saturday mornings, I can still hear the tinny theme song of ABC’s “Wide World of Sports.” I can hear Jim McKay’s voice as he announces … the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat.

I looked up at the sign in front of me: NFL MVP. “So that’s you?” I asked pointing to it. “You’re Mark Moseley?”

The man took a sip of his coffee and nodded. “And that’s a Super Bowl ring,” I said, looking at the thick gold band on his right hand and stating the obvious.

“Mmmhmm,” he said, holding it up. Someone came over then and Mr. Moseley regally rose from his chair and said, “I hope y’all come back and see us again.” And then to the man who joined him, he said, “She just moved from DC. She knows Charlie.” The boys held up their sticky fingers for me and I got up for some napkins and felt something else rise inside me. Maybe it was relief or maybe it was happiness and maybe it was the fact that I had felt seen by this man with the beautiful boots. Moving always has a way of making me feel invisible, as if by changing locations, I have erased some essential part of myself, some piece that the man with the Super Bowl ring just handed back to me.

I’m not who you think I am! I had wanted to scream at that receptionist, just as I had wanted to ask the NFL MVP, Who do you think you are? How little we think we are allowed. How much we think we need.

It was late in the afternoon so the boys and I left Sweet and headed back to our Hilton Home2 to find that once again, housekeeping hadn’t shown up. I set Oliver up with his first-grade workbook and gave Gus some crayons and construction paper. I unrolled my yoga mat in the space between the two beds. I knew I probably only had a few minutes, but I could do some sun salutations in that time. I could give myself back to myself.

Without my friends and the lush Virginia woods, without the comfort of the worn oak floors of my Virginia kitchen, without the hot Georgetown yoga studio, without the refrigerator full of kale and overflowing book shelves and a city to hate, who was I? I looked around the room at the things I had deemed essential: crayons, books, and Legos, a rice cooker and too many shoes, an expensive jar of red onion jam and a long flat sticky mat. How little I think I am allowed. How much I think I need to make up for this.

The discomfort of this discovery is fragile and sharp and I carry it the way you would a piece of broken glass or an armful of thorny roses, a burning match or a dying starfish, objects shaped like heartbreak, whose beauty and wreckage are inextricable. This move to Jacksonville has been a crucible I have stepped into, the heat and shimmer of concrete and sand a mirror to what lies inside of me: the elusive shadows of beauty and bright piles of wreckage.

I do a few sun salutations and then I walk over to Oliver. I put my hand on Gus’ neck and feel the lump there, the beautifully benign node. I remember the way my own heart beat a year ago when I took Gus to the pediatric cardiologist to check out his heart murmur. I remember the way I exhaled when the doctor told me that Gus had an innocent murmur, that I had nothing to worry about.

How lucky I am, I think, as I look around our tiny hotel room, how narrowly I have edged through those clear panes of disaster. I think of my penchant for drama and realize suddenly that moving is neither a disaster nor the end of the world. Disasters are the only disasters. The end of the world is the only end of the world. I stand still for a moment and listen to the boys tell me about their artwork. Gus’ healthy neck is bent over his paper and I see how little I need. I feel stuffed full of all all I have been allowed to have.

Uncomfortable

June 11, 2012 § 21 Comments

“No Meg, don’t hope it was a dream. I don’t understand it any more than you do, but one thing I’ve learned is that you don’t have to understand things for them to be.” – from A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle.

Jacksonville feels like a stain. It looks as dirty and tired as a bar after last call. We are staying in an extended stay hotel on Western Boulevard, the main business route, which is an aggregate of Old Navys and Olive Gardens, Walmarts and Wendy’s. The air smells like fried chicken and cigarette smoke and the sunlight bounces off all that asphalt. At night, shadowy packs of boys walk along the strip, their jeans low on their hips. Yesterday, I went to the grocery store and a man in a wife beater and flip flops leered at me. He parked his cart by the shelves of raw chicken thighs and made comments at women who walked by him. I turned sharply into the aisle with the detergent and held a box of Downey sheets up to my nose wondering how I ever could have complained about Washington, DC.

We will probably be staying at the Hilton Home2 until the beginning of August, when a house will be available for us on base. On the first floor of the hotel, a fitness center with a television is adjacent to a laundry room. Twice, I let the boys watch Disney Junior while I used the elliptical machine and slipped quarters into the washing machine. On Thursday, I struck up a conversation with another mother of two boys who is staying at the hotel because her house burned down last month. Marines in camouflage come out of other rooms on our floor, and from behind closed doors, I hear Southern accents and babies crying. I smell food being microwaved and Ramen noodles cooking. The night we arrived here, I had a quiet meltdown – conscious of the thin walls and my sleeping boys – thinking that at 39, I am too old to be living in a place that smells like someone else’s dinner. What was the point of the college degrees and all that striving? I thought back to another hotel room eight years ago in San Francisco. I was up all night helping the president of my company write her presentation and at five in the morning, I staggered off to Kinkos with it, thinking that finally, I was on my way. I would never in a million years have believed that I was on my way here to a town overflowing with soldiers.

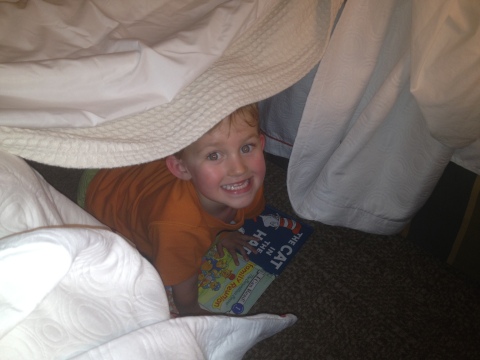

Each place I have lived during the last six years has taught me something. In Philadelphia, Oliver was born, ironically, two hours from the town I drove 3000 miles away from when I was 21. In San Diego, I learned how to be an adult, a mother, and a wife. In Ventura, I was taught how to trust my heart and to believe in goodness. Washington DC taught me how to be alone and then how to be with people. I spent a year with this guy:

And despite being so lonely for my first year there, things like this began to happen:

Tonight I went for a walk along Western Boulevard, a four-lane highway with sidewalks but no crosswalks. After a while, my walk began to feel like a game of chicken with the pickup trucks and I started back to the hotel. I passed by Ruby Tuesday and the House of Pain tattoo parlor, Food Lion, and a dilapidated barber shop. Even though it was nine at night, a couple with a small child was going into Hooters. I wondered briefly if I should be afraid and then decided I shouldn’t. I figured I could outrun an attacker, and if I couldn’t, I would put up a good fight.

Coming towards me was a group of young Marines. Maybe I wasn’t as different from them as I thought. I too am the kind of person who would fight to the death to protect myself, and as they approached, I realized I am ashamed of this. The boys looked so innocent as they walked by me, so young. I wondered if they signed up to serve and protect and if they were surprised when they found out what was asked of them. Or maybe they weren’t. When I looked up, one of them said hello with a smile that lit up his face. And then they all looked at me for an instant, their faces lovely with youth.

I thought about how complicated it is to serve, how the word protect sometimes also means kill and how much that bothers me. I thought that some of those young boys might be headed off to a war I despise while others might build a school somewhere or save a child. They would all be trained to shoot and a few might have to pull the trigger when it counted. I thought about how much I hate being part of the military, how paying the cashier at the market sometimes feels like handing over blood money. And I thought of how proud I am that my gentle husband is a part of the same organization I hate, because he has watched over his own share of young men with such devotion. How contradictory it is to protect a freedom, how much freedom is taken away to accomplish that, how the choice to serve takes away so many other choices.

And then I thought about the first Power Yoga class I took at Downdog Yoga in Georgetown. For the last six months, that studio has served and protected me, which I never would have thought possible after that initial class, which I wasn’t sure I could even finish. On that morning, last July 4th, as we celebrated freedom, I was trapped in my own thoughts of how thirsty and tired and miserable I was. “I’m so hot,” my mind kept saying. ImsohotImsohotImsohot.

Gradually – and despite my best efforts not to – I fell in love with Power Yoga and began to practice at the Downdog studio four times a week, at least. On my second to last class there only six days ago, Kelly, who was teaching, told us that if we were uncomfortable, then we were in the right place. “That’s what you’ve come for,” she said. “To be uncomfortable and to see what’s underneath.”

As I finished my walk under the streetlights on a sidewalk that was still hot, I felt the same way I did in that first yoga class in Georgetown. I don’t want to know what’s underneath. I don’t want to see how I judge, how I hate, how I break every yogic value I strive for. I want to know why I am here in this strange town near the ocean. I want meaning and reason. I want validation that I am in the right place.

But the night gives me nothing other than the smell of fried chicken and hot concrete, the sound of my own sharp panic and stale discomfort. And maybe this is why I am here: to be uncomfortable. To crack off another layer. To cleanse myself here, in this city that looks toxic and not a single bit lovely in the dark.