Boone

November 28, 2014 § 27 Comments

When it’s time to move on, there is no one to hold your hand. – Deb Talen, Ashes on Your Eyes

All I knew was that I couldn’t handle Thanksgiving this year. Fourth of July nearly did me in. It seemed as if every dad in the world was manning a grill or out in the driveway fixing something. One of my neighbors was in his garage blasting country music from his F150, and I felt oddly unprotected, even though I couldn’t identify the threat. The cicadas were whirring, the puppy was curled next to me, and the sun was reassuringly hot. Trying to keep things normal, we rode our bikes to the pool- that special summer domain ruled by stay at home moms and kids.

But even that was ruined with men. I sat on the edge of the pool with my sunglasses on while the boys jumped in. Nearby, a general’s wife was giggling and handing out paper cups of wine in a way that reminded me too much of high school. Later, the boys played with a neighbor on a slip and slide and then ran up the driveway with sparklers. The mosquitoes were fierce and I was panicky with a loneliness that was dark enough to feel dangerous. In my head, I mentally ticked off the holiday weekends that remained. Not Thanksgiving, I thought. There is no freaking way.

Last month, I booked a cabin in Boone, North Carolina for this weekend, an extravagant purchase that left me weak with relief. Until Tuesday night, that is, when I cursed my decision. After a busy week, I was finally throwing fleeces and underwear into a suitcase, trying to find large enough mittens and warm enough socks. My neighbor brought over snow pants and I was shocked to discover Oliver is big enough to wear my old hiking boots. Despite the fact that we were leaving, the same panic that haunted me in July was tugging at my ankles; the same creeping loneliness was draping its arms around my neck. I packed and cleaned until almost midnight and then loaded up the car with board games and down coats, suitcases and dog toys.

How foolish I was, thinking I could outrun a holiday.

Still, we got into the car Wednesday even though it was raining so hard, some cars were driving with their hazards on. After only a few miles, I was hunched over the steering wheel, wondering how this was all going to work.

By now, this is a familiar question, one I ask myself daily as I struggle with patience at bedtime or sit in the front of the room before a yoga class I am about to teach. So much of teaching is about being vulnerable, about walking into an empty space and hoping things are going to work out.

On Wednesday after I loaded the boys and the dog and the pretzels and the pears, we stopped at Starbucks. I had been too wiped out to make breakfast and the kitchen was too clean. We ran through the rain, and inside, the smell of coffee was a warm comfort. It was crowded and happy with that pre-holiday hopefulness, that maybe, this year, things would be better. I didn’t hear a woman calling my name until she grabbed my arm and said “Hey you!” It was Terri, a woman who works out at the gym the same time I teach yoga. She is small and wiry with spiky grey hair and eyes the color of sea glass. She was sitting with her friend Maria.

“Oh, these are your boys,” Maria said, touching my arm and smiling. “My girls are all coming home this year.”

“All four girls,” Terri added. “They live in New York. And oh my god – Maria is the best cook. Everything she makes.”

Maria smiled modestly and told me her husband was just home from deployment and that for the first time in a long time they would all be together. I felt her joy beginning to warm through my cold hands and feet.

“You have to try her carrot cake,” Terri said. “Oh my god, I will never eat carrot cake from anywhere else ever again.”

“Are you traveling?” Maria asked me and I said we were on our way.

“Is your husband here?” Terri asked and once again, I felt that shock that I am now part of this community, one that knows what it’s like to not know what will come next.

Last month, my neighbor was almost in tears because her husband was going on yet another training exercise to prepare for his deployment in August. “He’s going to miss Halloween for the fourth year in a row,” she said. “I’m so tired of this. I just want a normal life.”

“I know,” I said, and felt the familiar longing for predictability, agency, and home. Last week, Scott called and told me he just spoke to his detailer – the person who tells him what and where his next job will be. For five years we have been trying to get back to the west coast, and each time, we get farther away from my idea of home. I miss California so keenly, it feels like a phantom limb.

“Well, “ Scott had said. “It’s now between San Diego and one other place.”

“Oh jeez,” I said, because it’s always been between California and one other place. And we always go to that other place. “So San Diego or -?”

“Guam,” Scott said and inside, my mind said I can’t live in Guam. It will be a disaster. And then I remember that it will probably be fine. Because it’s always been fine, at least after a little while, anyway.

“We’ll find out soon,” he said. “I’m pushing for California.” But we both know it’s mostly out of our hands.

I told Terri Scott was in Bahrain and we were running away to Boone. Terri gave me a high-five. “You’re breaking the mold girl! Good for you.”

As we left the store, an older man with a rain-spattered Life is Good shirt held open the door for us and we stood under the outside awning, watching the rain bounce on the pavement.

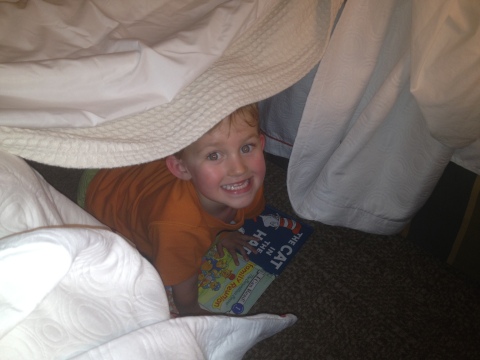

I did not yet know what the day would bring. I had no idea that outside of Durham, I would drive through a soup of fog and truck spray and rain or that outside Charlotte, the skies would clear, revealing a ragged V of geese. I didn’t know I would stop for gas in a place so scary, it was like something from a Stephen King novel or that the flat land of eastern North Carolina would be so comforting: the low cotton fields and the leaning shacks; the plywood signs announcing boiled peanuts and sweet corn and “tomatos.” (They always forget the “e”). I didn’t yet know that our cabin would be snug and warm and I didn’t know that Wags would be so scared of the stairs I would have to carry her up and down every time we took her out. I didn’t know that for the first time, I wouldn’t get lost, that we would find the hiking trail I read about online and that it would snow as if on cue. I hadn’t yet discovered that pumpkin pie and hot chocolate were the only Thanksgiving foods we would need and that all the things I thought were so important would turn out not to matter very much after all.

Then, I only saw that it was raining hard. I only hoped things were going to work out. I only knew I had been trying really hard to run away from things that are impossible to avoid. Thanksgiving, deployment, the unknown.

“Wait here,” I said to the boys, “And I’ll bring the car around so you won’t get wet.”

“No,” they both said, protesting loudly.

“OK,” I said, watching the rain slant sideways in the wind. “We’d better go.” I took their hands and we ran towards the car, towards the mountains, towards the day.

41

January 28, 2014 § 30 Comments

The number forty is highly significant across all traditional faiths and esoteric philosophies. It symbolizes change – coming through a struggle and emerging on the other side more enlightened because of the experience. – Dr. Habib Sadeghi

Usually, I begin my yoga classes with child’s pose or a simple seated meditation, but really, meditation is too strong of a word. We breathe in. We breathe out. And inevitably, a Marine in the back of the class is trying so hard not to laugh out loud that he is silently shaking. Usually, I have to close my own eyes and press my lips together so that I don’t start laughing myself.

It’s always a bit awkward in the beginning when I’m asking them to come into cat cow pose and then downward facing dog. Some people are looking around and vigilance pulls up the chins of others. No one is breathing and you can feel the tension rising off bodies like steam.

Then I ask them to come into plank pose, and like magic, all the giggling stops. After about ten seconds in plank, the vibrations in the room begin to settle. After thirty seconds, the disparate streams of energy begin to gather. After a minute, the quiet comes down like a curtain falling.

I don’t have them hold plank to prove anything, or even to quiet the laughter. There is something so familiar about that pose for Marines and athletes – something almost comforting about being in a high push-up. And yet there is something else about plank that gets right to the heart of our own vulnerability. Maybe it’s that our pelvis wants to collapse in a way that would showcase our weakness. Maybe it’s that plank pose demands us to soften the space behind our hearts. Or maybe it’s the quiet of the pose itself, the stillness required to hold ourselves straight and stare at a single spot on the floor.

After plank pose, it’s different in the room. I can say inhale and 30 sets of lungs breathe in. I can say exhale and 30 sets of lungs breathe out. I can place my hands on someone’s shoulders and they no longer want to flinch.

It was my birthday this week and I have been thinking an awful lot about vulnerability. 41 is a year that lacks the spunk of the thirties but also the dire nature of that four-oh milestone. 41 is not yet old but definitely no longer young. 41 is a bit like jumping into the shallow end of a freezing cold pool and hopping up and down, your arms over your head. 41 is about being in it but just barely. It’s about stopping by the mirror and knowing that you still look much the same as you did at 20, but undeniably, your skin is thinner and creased. What is left may look the same, but it’s only a veneer of who you used to be, and soon that will be gone too, and the true self – the real face that reveals our own creased and softened souls – will emerge.

41 feels a lot like being in plank pose.

Most of my fortieth year was spent on my back, staring up at the clouds that seemed to be rushing by too quickly. Last winter, I woke up in the cold sweat of panic attacks and during this past summer, I couldn’t sleep. 40 required waking up to the fact that I was living in a way that was not sustainable, that I couldn’t forego rest anymore in the name of getting things done, that I needed to stop saying yes when I meant no, and that I desperately wanted to stop asking for permission. Chocolate and wine were no longer staving off that terrifying feeling of fragility, and the warning hum underneath was becoming so loud I felt a little crazy. Last year, a line from Hamlet wove its way into my days: I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams.

For 39 years, what I wanted more than anything was to be tough. I would rather be angry later than vulnerable now. It’s easier to be the master of my own fate than to place it into someone else’s palm and close their fingers around those thin shards of glass. I had thought that toughness would scare the fear away. But it turns out that fear stays anyway and makes you want to giggle. It makes you want to yell or run or it wakes you up in the middle of the night and squeezes at your heart.

People talk about vulnerability now as this great thing and I suppose it is. But what they don’t often tell you is that one part of vulnerability is to take a good and honest look at yourself, which feels a bit like sticking your head into the mouth of a monster. Asking the questions is only one part of the equation. It’s sitting still with the answers that’s the kicker. There is the way that I think I am in the world, and then there is the way I actually am.

Sometimes I wonder how on earth I became certified to teach yoga. Of all the experiences in my life, teaching renders me the most vulnerable. It feels like taking off my skin. Before each class I feel like Hanuman, when he ripped open his chest to show Ram his devotion. Ram, Ram, Ram beat his heart.

I am working with Rolf Gates on my 500 hour teacher training, and in our last meeting via Skype I shared some of my challenges with teaching, mostly, that I don’t feel I am up to the task. Rolf laughed after I was finished and said,”Welcome to your first ten years teaching yoga,” which I found oddly comforting. He could have easily been saying, Welcome to your forties. And then he told me that teaching is like pointing at the moon. What’s important, he said, is that our students understand the moon.

The way I see it, there is no way to understand the moon without first standing alone in the dark. There is no way to understand anything unless you pay attention to the way it waxes and wanes, to the way it turns its back to you or slips behind a cloud. The glow and the radiance: it’s only a fraction of what it really is.

About three years ago, I wrote that I felt as if I was on the precipice of something, but couldn’t see far enough down to know what it was. Now, I see that what I was gazing into was the mysterious space that houses our hearts. That my task is to simply crouch in the doorway and pay attention to the storm, to the call of the wind and the violent lashing of the branches. My job at 41 is to sit in the eye of the hurricane, rip open my heart, and listen.

Choice

October 28, 2013 § 40 Comments

“Apprentice yourself to yourself, welcome back all you sent away.” – David Whyte

I am approaching this space with chagrin, a sense of hands wringing in the space at my center. In August, I vowed I would write here more, and once again I have broken my word, those promises I make to myself that are more fragile than they should be.

In the spirit of true disclosure, September and October have been a bit of a boondoggle around here, and when things get tough, I tend to hide. Or, I tend to make myself so busy that I have no time to sit still, or to think, or to begin the clumsy and tedious process of sorting through words, picking them up and throwing them back as if they were tiles in a box of Scrabble.

I love the month of October, but it has an edge to it for me now as it is the month when we begin to get a hint of our next orders – Scott’s next assignment – the place to which we will be moving next. Every odd year in October, I get a whiff of endings as the leaves fall down and I need to prepare myself for the leaving and then, for the arriving. This year, I was relaxed about it and far too confident. We had thought this would be the move where we prioritized where we wanted to live rather than the right career move. This was going to be a move for family and not solely for the job, and I was excited about the liklihood of us moving to either The Netherlands or back to California, which is the place where I feel most at home.

So, it was a bit of a sucker punch that the Navy came back with two options, each requiring Scott to deploy for a year. He will choose between Bahrain and Djibouti and then the Navy will send him to one or the other, regardless of his choice. “Jabooty?” I said to Scott when he called me from work. “I don’t even know where that is.” It sounded like the punch line to an old Eddie Murphy joke.

“It’s in Africa,” he said, “Near Somalia,” and I said what the hell.

For the last month or so I have been wondering how on earth I will parent our two boys alone and how I will shore us all up enough to get through a year without Scott, whom we all adore and lean on to a ridiculous extent.

Right now, I can’t imagine it.

Two weeks ago I went to open the fridge in the garage and had a strange sensation of being watched. I glanced up and saw the beady eyes of a tree snake, its body wound around the freezer door. I ran back into the house calling, “Scott! Scott you need to come out here now!!!”

Last Friday, I discovered there was a mouse living in the seats of my car and I almost had a heart attack. I called Scott who was on his way to give a speech and cared not a wit about the fact that rodents were living in my car, so I texted the strongest and most stalwart of my neighbors. “I’ll be right over,” Tammy texted back, and together we tore apart my Prius and found that my emergency granola bar stash in the trunk had been raided, the wrappers shredded and stuffed into the interior of the back seat.

My other neighbor across the street, Miriam, drove by on her way home and leaned out the window of her minivan. “What are you guys doing?” she asked. When we told her, she parked in her driveway and walked over with her four-year old daughter and her yellow lab. “If it were me, I would get a new car,” she told me and I explained that getting a new car would require driving this one someplace first, and I wasn’t about to get in.

“Really?” Miriam asked. “But you’re so brave.”

“What gave you that idea?” I asked, and she shrugged. “I don’t know. You had a snake in your garage. Or maybe it’s because you have boys.”

“No,” said Tammy, who has a daughter and a son. “Boys are easier.”

And so the conversation turned again to the every day ordinary, as it always does, and Gus circled around us on his bike. We were gathering up the shredded paper and my reusable grocery bags, now ruined with mouse droppings, and I felt a tide of panic begin to ebb in. I am used to this now, the anxiety that seeps and slides until it rises up to my throat. “How on earth am I going to get through a year on my own?” I asked the women next to me and instantly felt silly because these women were Marine wives. Scott was gone for 8 week intervals during the first two years of our marriage, but these women have already been through more than five deployments each, their husbands away more often than they are home.

“You’ll call us,” Tammy said matter of factly as she slammed my trunk shut, and I felt something sink down and land.

“Yes, you’ll call us and you’ll get a dog,” said Miriam and then told me about the time a raccoon jumped out of the garbage can at her while her husband was gone. “If you’ve ever wondered why I take my trash out at noon, now you know.”

Gus once again circled our piles of seat fluff, and then the school bus pulled up and all of our children spilled out. Oliver and Gus got on their scooters and rode over to their friends across the street and Miriam’s girls were excited to add another “nature story” to the newsletter they are creating for the neighborhood, entitled The Saint Mary Post. “Mrs. Cloyd,” Miriam’s oldest said breathlessly as she pulled a notebook out of her backpack. “What was your reaction when you discovered mice were living in your car?”

What is my reaction to anything? I thought to myself. Out loud, I said, “EEEEEEEEEK!” which Laura Fern wrote down, her pencil pressing hard into the paper.

I’ve started running again after a slew of injuries, but I suppose it’s more accurate to say that I jog slowly for a few miles. The other morning, after the boys got on the bus and the tide of panic was rising up my ribcage, I laced up my shoes and set out. I thought about my reactions, how usually they are negative, because most of the time I am afraid. Most of the time, I am the opposite of brave. On that morning jog I was angry about the deployment, angry because this was supposed to be the move where I got to choose. This was supposed to be my turn. Mine. Not the Navy’s.

Well then, said a small voice inside me, Choose this.

“No,” I said back, but then I felt that softening again, the landing and I wondered if I was allowed to choose something I didn’t want, if it was even possible, if maybe, choosing has nothing at all to do with wanting. I don’t want a mouse in my car or my husband to leave. I want what I want and inside me, wanting has always been fierce, its claws always pulling me away and out and up. Look at this, wanting says, racing up to me on scurrying feet. Isn’t it lovely?

And now I am trying to put the wanting aside, which is something new for me. Shh, I am telling it, Not now. I use soothing words like hush and sometimes a firm word like stop. I am practicing.

Yesterday I had to teach yoga, which requires me to drive. I went out and stood in front of my car. I opened the door and removed the empty mouse traps Scott had set the night before, but their emptiness proved nothing to me. “I think it’s gone,” Scott had said as he looked under and around the seats, but I wasn’t buying it. You never know when those feet will scrabble up your spine, when those sharp teeth will sink in, grabbing your attention away and out and up.

I got in the car and fastened the seat belt. “Hello mice,” I said into the meaningless quiet and then I got the willies just thinking about them. I wanted a new car. I wanted another option. I wanted things to be different.

And then to myself I said, Shh. Not now. Drive the car.

I am still practicing.

Atonement

September 18, 2013 § 19 Comments

Yom Kippur: Going into the innermost room, the one we fear entering, where fire and water coexist like the elemental forces in the highest heavens our ancestors, the ancients, observed in awe. – Jena Strong

Last week was Yom Kippur, which is a holiday I love even though I am not Jewish. My parents are Catholic – my mom the only one practicing – but growing up, we were invited to enough Passover Seders that hearing the words: Baruch atah Adonai elohaynu melech ha’olam instantly reminds me of spring. I don’t celebrate Yom Kippur but I wish I did. We should all have a day to look inside, to take stock and be quiet with what we find.

As a Catholic, I went to confession. I always hated confession, the way I had to pull that velvet curtain back, kneel down and tell the priest my sins. I lived in a small town and it was a pretty good bet he could recognize my voice. Bless me father for I have sinned, I always began, and he usually gave me an Our Father and three Hail Marys to say for penance, which I did after I left the vestibule. This time, I would kneel in relief, bowing in the bright light that filtered through the stained glass windows of the church.

In the chakra system, the element of atonement is in our throat, where we express our ability to choose – what we say yes to and what we say no to. Do we choose our own will or a divine will? The fifth chakra is a yogic version of Yom Kippur, or as Caroline Myss so beautifully describes it, a place where “we call our spirits back.”

Two weeks ago, I got into the car after a yoga class I taught at the fitness center on base. I truly love teaching on base even though we practice on the gritty floor of a cold, group exercise room. Before class, I turn off the flourescent lights and the fan, the strobe lights that are usually still flashing from the Zumba class that ends right before my own. I place 12 battery-operated candles at the front of the now-dark room and unroll my mat. I plug my iphone into the stereo and play Donna DeLory or Girish – music that does nothing to tamp down the blare of Taylor Swift from the gym or of the sound of weights being racked right outside the door. I love teaching in that gym, which smells like an old boxing ring and is always jam packed with Marines. My Tuesday yoga class is usually full due to prime scheduling time, and I leave there feeling buoyed up and overflowing.

That Tuesday, two weeks ago, I sent a text to my babysitter from the gym and then got in the car and headed home. For some reason – maybe because I felt particularly immune that day or maybe because the boys weren’t in the car – I hit the redial button on my phone and put it on speaker. Scott had ridden his bike to work that morning because his car battery died, and I thought I would be charitable for a change and see if he needed me to bring him anything. I picked up the phone and said hello and 30 seconds later a police car was behind me, his lights flashing. I pulled over, instantly beginning to tremble. Oh my God. Oh my God. Ohmygod. A few months ago, one of Scott’s guys had gotten pulled over for talking on his phone while driving and he lost his driving privileges on base for 30 days. I couldn’t lose my driving privileges. How would I take Oliver to soccer? How would I get to the grocery store? How would I teach yoga? Losing driving privileges on base is pretty much like house arrest.

I watched in my side mirror as the Marine police officer got out of his car and ambled over to me, pushing his sunglasses onto the top of his head.

“Ma’am,” the officer said, and nodded at me through my open window. “Do you know why I pulled you over?”

“Because I was speeding?” I asked hopefully.

“I’m afraid not,” he said and then asked for my driver’s license and registration. With trembling hands, I handed him my credit card. “Ma’am?” he asked again, and I fumbled for my license. I gave it to him and he held it up for a second. “You were using your cell phone without a hands-free device and that’s illegal on board Camp Lejeune.” I watched the muscles in his forearm twitch. He couldn’t have been older than 25, and he looked as though he could crush my Prius with his bare hands.

And then I did it. “I wasn’t talking on my phone,” I lied, my heart racing, thinking about what it would be like to not be able to drive for 30 days, to be stuck way out at the end of Camp Lejeune. “I was plugging it into my stereo system.”

I looked over at the passenger seat where my yoga mat rode shot gun next to the blankets and blocks I bring for the pregnant woman who comes to class. The lie sat there like a hairball.

The officer nodded graciously. “Maybe that’s the case Ma’am,” he said. “I saw you holding your phone up and your lips were moving, but maybe you were singing along to the music.”

I closed my eyes and felt my face get hot.

“This won’t affect your driving record,” he said kindly. “But you will have to go to traffic court. The judge will decide if you’ll lose driving privileges or not.” He gave me a tight smile. “Your record is pretty clean, so my guess is not.”

He let me go with a pink slip of paper and a number to call and I drove home, feeling shame rise up to my scalp. Who was I?

That afternoon I called Scott in tears and I texted two friends who told me everyone lies, that it wasn’t a big deal, but it didn’t make me feel any better. The next day on the way out to the bus stop, my neighbor across the street called out, “Hey, you made the police blotter!” She seemed to think this was hilarious. My next-door neighbor’s husband was there too and he laughed.”You’ll be fine,” he assured me. “I know the magistrate at traffic court and he’s a nice guy.” The truth was, I didn’t really care about traffic court anymore or even about losing my driving privileges.

Last year, right after Christmas, I was practicing handstand against my bedroom wall before I went to teach a yoga class. Because I have been working on balancing in handstand for the last four years, this is not usually a problem for me. But for some reason, on this night, I totally freaked out once my hips were off the ground. Ohmygod, I thought and my legs began to flail before my foot banged on the dresser and my knee crashed into the floor. It hurt so much that I could only curl into a ball on the floor and try not to throw up. My pinky toe was black for a week and my knee still hurts if I put too much weight on it.

After leaving the bus stop that day – my neighbors calling our reassuringly that it would be OK and don’t worry – I thought about that handstand. That’s who I am, I thought. I am someone who completely loses her shit when her back’s against the wall.

On Monday, after I heard about the shooting at the Navy Yard, I texted and emailed some friends. My former roommate told me that her husband was OK but that he had been on the fourth floor and barely made it out. He spent a few hours that morning in lockdown with a woman who had collided with the shooter. She begged the shooter not to kill her, my friend wrote to me, and for some reason he spared her life. I thought about Scott, who was at the Navy Yard several times a month when we lived in DC. Even I had been there a couple of times to meet with a lawyer to finalize our will. It’s only a few blocks from the Metro stop on M Street, close to the ballpark, smack dab in the middle of the city.

For most of the day Monday, I tried to find a reason for the tragedy, for something to reassure me that we don’t live in world where survival is a total crap shot. But guess what about that.

On Monday night I had to teach yoga at 6:30 and I pretty much had nothing except an essay from David Whyte called “Ground.” Yesterday – a Tuesday – I drove to the fitness center after the bus left. I lugged my bag of candles into the cold group exercise room and turned off the lights. Because I am a mostly selfish person, I decided to focus the class around our throat chakra. When everyone was lying still on their mats, I told them about my day on Monday, about how my own attempt to find reasons for the senselessness of the tragedy at the Navy Yard looked a lot like blame: If only they had checked the trunk of his car. If only we had better gun laws. If only.

I also told them something I believe is true, which is that we are all connected. That the only way to change the world is to change ourselves. If we want more kindness in the world, we need to be more kind to ourselves. If we want there to be less judgement in the world, we need to stop being so hard on ourselves. Thoughout the class, we opened our throats and softened our jaws. We did side plank and arm balances, followed by child’s pose. “Notice if you are judging yourself or comparing yourself to someone else,” I said to them, but really to myself. “And if you are, then simply call your spirit back.”

I was shaky and a bit off in class. When I was assisting a student in Warrior III, we both stumbled. I kept thinking about the woman whose life was spared. I kept thinking about my lie. I kept thinking about how connected we all are, that there are no bad guys and no good guys. There is only us.

Last night, a chill slid into the air. September, which has been clunking along so far with its heat and its bad news seems to be slanting towards fall after all. Under the full moon, I watched a few leaves blow around in a circle and I thought of Macbeth. Let not light see my black and deep desires. And yet, it’s the light that matters. And for some reason, he spared her life.

Today, I had to report at traffic court at 7 AM. I had to stand in front of a judge with my pink slip and tell the truth. “How do you plead?” he asked me and I said Guilty. But it doesn’t really matter about traffic court or even the judge. In the end, there is only us.

Ground – David Whyte

Ground is what lies beneath our feet. It is the place where we already stand; a state of recognition, the place or the circumstances to which we belong whether we wish to or not. It is what holds and supports us, but also what we do not want to be true; it is what challenges us, physically or psychologically, irrespective of our abstract needs. It is the living, underlying foundation that tells us what we are, where we are, what season we are in and what, no matter what we wish in the abstract, is about to happen in our body, in the world or in the conversation between the two. To come to ground is to find a home in circumstances and to face the truth, no matter how difficult that truth may be; to come to ground is to begin the courageous conversation, to step into difficulty and by taking that first step, begin the movement through all difficulties at the same time, to find the support and foundation that has been beneath our feet all along, a place to step onto, a place on which to stand and a place from which to step.

GROUND taken from the upcoming reader’s circle essay series. ©2013: David Whyte.

Thin

January 22, 2013 § 20 Comments

Well I better learn how to starve the emptiness. And feed the hunger. – Indigo Girls

I am not proud of how I felt when I first read about Asia Canaday. Katrina Kenison linked to this letter on Facebook which Jena Strong posted on her blog. The next day, Christa posted it too, these beautiful writers forming a circle around Jena and Mani and Asia, asking the rest of us for help in the form of a dollar or a prayer.

I am embarrassed to say that instead of joining the circle, I circled around it. I shut my eyes and shut my computer, feeling anger well up inside of me, maybe even fury. Just eat, I heard a voice in my mind say and then I was overcome by an emotion I can’t even name and I had to sit down.

It doesn’t take a genius to realize that I was actually furious with myself for doing the same thing Asia is doing now. When I was 16, I ate as little as I could, getting so thin that sometimes my legs became bruised from sleeping. I try not to think about those days, about the pain and helplessness I made my family go through. I try not to think of the way people used to look at me, their eyes wide with a certain kind of repulsion.

I’m angry too that this is still happening. After I clattered catastrophically through my own disordered eating, I turned away from the topic entirely, choosing to believe that childhood obesity was what we had to worry about now, not anorexia. Mani’s letter made me open my eyes, reluctantly, to the truth that in addition to living in a country with epic obesity and great starvation, 24 million people suffer from eating disorders, which have the highest mortality rate of any mental illness. Clearly, we are a nation with big issues around food.

And yet, this is not an issue about food or even hunger but about our beliefs of our own worth. Maybe I’m wrong but I think all eating disorders are slightly different manifestations of the same problem: a conviction that we don’t deserve to be here, a kind of longing to disappear, by either literally shrinking ourselves or by hiding under layers of fat. This is how much someone who is anorexic is suffering: starvation is preferable to the emotions she or he is feeling. The feelings are so enormous and out of control that self-inflicted pain feels better.

We can do the usual things I suppose. We can give money and support research and stop asking if this dress makes us look fat. But I think what might be even more powerful is to look at the ways we starve ourselves on a daily basis, even if we don’t have an eating disorder. Every time we tell ourselves that we can’t take a break just yet, or we don’t deserve that job, each time we eat a sandwich standing over the sink or resist the urge to sing out loud. When we tell ourselves that that we aren’t strong enough to enter that race or leave that guy, we send clear messages to ourselves and the world about what we believe we are allowed to have. Every time we ignore what Geneen Roth calls “the knocking on the door of our heart,” we are finding a way to disappear, to stay small, and we are passing this on to each other like a plague.

Of course I am not talking about you but about me. I still have very set ideas about what I need to get done before I can go to bed at night. I want to exercise and meditate and do yoga. I need to squeeze in time to write and time to make dinner, pack lunch. I have to clean the bathrooms and hey, are these pants getting tight? I received an email from a friend today whose family was recently taken down by the flu. She wisely told me she was going to try to find a way to get the space and the time she has when she’s sick so that she doesn’t have to get sick to have it. I felt my heart lighten as I read this and then grow heavy again at the ways I refuse to receive what is always on offer to me like an open palm: a breath, a kind word to myself, space and time, even if it is only a moment.

In Buddhism, there is a character called a Hungry Ghost, a creature with a tiny mouth and a bloated distended stomach, a narrow throat that makes eating so painful, the ghosts haunt each generation with their empty bellies, with their ravenous unmet needs, with their boundless, aching hungers. Some Buddhists leave food on their alters for the ghosts, delicacies that satisfy an unnamable longing. Learning about this brought tears to my eyes. Is it possible that we could be this compassionate to each other? To ourselves?

I am going to echo Jena’s request that you leave a dollar or a prayer here for Asia and her fiercely loving mother, Mani. I am also going to suggest that we take an hour or a minute to honor our own hungry ghosts. Maybe we can sit down to eat breakfast or drink the whole cup of coffee (while it’s hot!!). We can carve out a few minutes to gaze at the sky or down at our toes. We can tell ourselves that we are allowed to dance terribly, that what we write can be awful, that we deserve that job, that we can ask for that hug. We can gently remind ourselves that eating kale doesn’t make us a better person, that we are allowed to go to bed at eight o’clock, that we don’t have to finish the whole thing, that there will be more, always enough if we take time to listen to the delicate thrum of our hearts, if we pause for a second to tell ourselves – even if we don’t believe it yet – that we deserve for our life to be good, that we already are good enough.

Freedom

September 10, 2012 § 16 Comments

“Sometimes life hands us gift-wrapped shit. And we’re like, “This isn’t a gift, it’s shit. Screw you.” – Augusten Burroughs

“Well Jacksonville’s a city with a hopeless streetlight.” – Ryan Adams

This has been a very difficult summer for me for reasons that have more to do with my own mind and less to do with what actually happened to me. When we moved from Washington, DC to Jacksonville, North Carolina, we knew we would have to wait at least six weeks until a house was available for us on the Marine base here. I just didn’t think that at least six weeks would actually stretch out until fourteen weeks, longer than a Southern summer, all of us sleeping in one room from Memorial Day until weeks past Labor Day.

I am trying to realize how lucky I am to have the privilege of staying in a hotel for this long, and if you could see this town, you would understand. It’s the kind of place where a steady stream of women and children file into the WIC office, and the Division of Employment Security always has a few men sitting on the curb outside, their arms wrapped around their knees. Driving from our hotel to the base, where Oliver just started first grade, we pass countless pawn shops and tattoo parlors, a Walmart, a Hooters and a windowless, cinderblock “gentlemen’s” club called The Driftwood. Before I arrived in Jacksonville, I didn’t believe places like this existed outside of New Mexico or movies starring Michelle Williams. I recently discovered that one of my favorite musicians – Ryan Adams – grew up here, and as I again listen to him crooning those heartbreaking lyrics, I am not surprised. Jacksonville, North Carolina may be the saddest, hottest, dirtiest town I have ever set foot in.

In early August, one of the housekeeping staff stopped me on the way down the hall. She held out her palm and asked me if the small, brass, semi-automatic bullet in her hand was mine. “Um, excuse me?” I asked, feeling my jaw drop open and then I shook my head. “No,” I said, “No, we don’t have a gun.” Jesus, I thought as I walked away and then I turned around. “Where did you find it?” I asked and the woman told me that it was right behind the bed where my sons have been sleeping.

Later that month, I took the boys to the indoor pool one afternoon. We did this a lot as Scott was traveling for a couple of weeks and it rained every day he was gone, the sodden hem of Hurricane Issac dripping over Jacksonville. On that grey day, Gus jumped into the pool, into my arms, before I was ready and his head banged into my eye. “You’re bleeding!” said another woman in the pool so we all got out. By the time we were back in our room, I could feel my eye swelling. The next day – Oliver’s first day of school – there was no amount of concealer that could cover the purple and green lump under my eye and the gash right above it. I met Oliver’s teacher noticing her eyes flickering with concern as they focused on my shiner, knowing that there was nothing I could say that wouldn’t sound as if I was making an excuse for something. I told Scott it was a good thing he was out of town.

I’m not who you think I am, I wanted to scream, which has been sort of a mantra of mine all summer, mostly to myself. Since June, I have been trying to convince myself that I am not homeless or a failure or a lousy mother but it’s been challenging as I keep finding myself in situations where it’s easy for people to take one look at me and get the wrong idea. All of my life, I have been an incredibly judgemental person, and this summer, my judgements were turned inward, towards myself. Or maybe that’s where they’ve been all along.

I never thought I would become a military wife. I was born in the early 70’s, in the heyday of Women’s Lib, and as a teenager, I swore I would never let myself be defined by a man. A military wife was pretty much the last thing I imagined, and there is a small part of met that feels like I let someone down. This summer a bigger part feels like I’ve let my kids down, tearing them from their friends in Washington, DC and our big house there and sticking them in a single room with a bag of Legos each. Oliver, especially, has had a tough transition from his Waldorf school to his Department of Defense school, where already, he is expected to keep a journal. Tonight he had to write a paragraph about what freedom means to him.

Freedom. In Jacksonville, the word “Freedom” is everywhere: on teeshirts and bumper stickers and even on the sign welcoming you to Camp Lejeune. “Pardon Our Noise,” it reads, “It’s the Sound of Freedom.”

In yoga, freedom means to be released from the chains of our mind, and this summer, living in a tiny box, I have seen how chained I am to my own idea of how things should be, how chained I am to my ideas of how other people should be, to how I should be. What is true is that I have exactly what I want: I married my best friend, a man I am still madly in love with after a decade of being together, and I am able to stay at home with my kids, which I am lucky to be able to do. Scott supports my yoga habit, stayed home from work one day a month last year so I could go to my yoga teacher training, and he doesn’t complain about eating kale or Gardein Chik’n, which I have been making often in our hotel.

What is also true is that getting what I wanted doesn’t look the way I thought it would, and I get upset about that, some strange combination of guilt at not having a job and resentment that I have to follow someone else’s orders and traipse after a man. Every other place we have lived – San Diego, Ventura, Washington, DC, Philadelphia – I was able to pretend that I wasn’t a Navy wife, that I had nothing at all to do with the war waging in a far away desert.

In Jacksonville, I can’t hide anymore. The town is crawling with soldiers. You can’t turn your head without seeing a Semper Fi bumper sticker or a Marine Wife window decal, a gaggle of young recruits sauntering down Western Boulevard, or a young man in a wheelchair, empty space where his leg used to be. Something about this town has brought me to the bottom of myself, to the place I have been avoiding for years, covering up with power yoga and running, volunteering and a second glass of wine.

And yet, there is a relief in the crumbling of an unstable structure because once the last wall falls, you find yourself sitting in the middle of a dusty, empty space that feels a bit like what freedom might feel like if freedom didn’t stand for guns or bombs or a country’s foreign agenda. Once you find yourself on rock bottom, there is nowhere left to go. You have already eaten the cupcakes and run the miles and held Warrior II for days and nothing has worked. Nothing has changed except the myriad ways you have thrown yourself against the walls. And then, one day, after cursing the sun that beats down upon the ruins, you finally sit up and survey the jagged thoughts shredding your heart. You say, “Well then. This must be the place.”

Jacksonville is that place. Our stale and musty hotel room is that place. Oliver’s new-school anxiety is that place as is my acquired and inherited shame that I will never be good enough. In his yoga DVD, Baron Baptiste says, “That which blocks the path is the path.” This summer, I have been punched in the face with my own resistance, with my tight-fisted grip on the way I think things should be. I have been handed bullets and black eyes and I keep forgetting that these are the gifts. I forget that the lessons are handed out in the trenches, in the foxholes, in the dust of crumbling temples. I am discovering that wisdom hides in the most wretched of places, buried deep in the towns with the hopeless streetlights.

Click here to hear Ryan Adams sing about his hometown, Jacksonville, North Carolina.

Lumps

July 2, 2012 § 11 Comments

Too often we give away our power. We overreact. We judge. We critique. And we forget to breathe. – Seane Corn

In mid-June, Scott’s parents flew in from Oregon and my own parents drove down from Pennsylvania to visit us here, in North Carolina and to attend Scott’s change of command ceremony on Camp Lejeune. Because I couldn’t possibly imagine our families in this strange extended-stay hotel with us, we rented a house on Topsail Island for a week. It was such a relief to be able to open a door and let the boys run outside, to sit on the beach without driving there, to walk near the warm waves at night and wake up and do yoga on the deck outside our bedroom.

And then it was time to leave. My little blue Prius was so full of suitcases and sand toys, cardboard boxes full of peanut butter and oatmeal, raisins and spirulina powder, a pint of berries and an eight-dollar jar of red onion confit I bought at Dean and Deluca in Georgetown before we moved because I had to have it. The boys could barely fit into their car seats, and on the passenger seat next to me was a laundry basket full of bathing suits, my Vita-Mix blender, a Zojirushi rice cooker, and a Mason jar full of the seashells we found on the beach.

It was a little after eleven in the morning. It was past the time we were supposed to be out of the beach house and hours until we could check into our hotel. We had already spent the morning on the beach, and as I steered the heavy car out of the driveway, I realized I had nowhere to go.

You’re homeless, you know, said The Voice inside my head. You are 39 years old and you have no place to live.

I am not, said the Other Voice. I am not homeless.

And yet, you have no home, said the Voice, So what would you call that?

We spent some time at the Sneads Ferry library and checked out some Magic Treehouse books on tape to listen to in the car. We drove to a park with a big boat launch in Surf City and boys watched with fascination as pickup trucks hauling fishing boats expertly backed up to the water and set their boats free. We watched a big blue crab walk sideways in the brackish water and the boys threw leaves at the tiny fish that shimmied near the docks. We went to a pizza place for lunch because I knew there were clean bathrooms there and we went back to the beach where the boys were cranky and kept grabbing each other’s shovels.

The night before, when we were still in the beach house, I felt a lump on the side of Gus’ neck and my heart leapt up into my throat. I asked my father-in-law to take a look and he told me it was nothing. “Don’t waste a doctor’s time with that old thing,” he said, which comforted me greatly, but still, while the boys stole each other’s beach toys on that homeless day, I was on the phone with a pediatrician’s office. “Why don’t you come in tomorrow?” the receptionist asked me and I felt my unreliable heart writhe and squirm again.

I gave the receptionist my name and my insurance information. She asked for my address just as Gus hit Oliver on the head. We had gotten a PO box the week before, but I hadn’t memorized it yet, and it was clear that if I didn’t get off the phone, one of the boys would hit the other with a plastic dump truck or the bright yellow buckets I bought a few days earlier. “I don’t have it right now,” I told the receptionist. “We just moved here. Can I bring it tomorrow?”

The next day, we arrived early for Gus’ appointment. The waiting room was nearly empty and as I was filling out form after form, a nurse came out and stood by the receptionist. “She didn’t have her address yesterday, so I couldn’t start the file,” I heard the receptionist say in a loud whisper. “Honestly who doesn’t have an address? Who are these people?”

I felt tears start in my eyes and my whole face ached with shame and fury and a feeling of desperation so great that I wanted to jump in my car and watch the entire state of North Carolina recede in my rear view mirror. Hey, I wanted to say, I can hear you. Instead I said, “I’m almost finished,” and watched the receptionist jump and turn around. I walked up to her desk with my completed forms but couldn’t look at her, my face hot with the shame of having no address, no place to go, no home.

Afterwards, when the doctor told me I had nothing to worry about, that the lump was just a swollen lymph node, I was so relieved I took the boys for ice cream. The main road into Jacksonville – Western Boulevard – is particularly ugly, but the week before, on a walk, I found a little ice cream place called Sweet, which looked brand new and cozy. It was sandwiched between a Five Guys and a Popeye’s, but inside Sweet were velvet couches and soft chairs, a coffee bar and an old-fashioned ice cream counter. A sign on the wall announced that there would be a benefit tomorrow and NFL MVP Mark Moseley would be signing autographs and footballs.

The boys and I sat on a couch and ate our cones and a few seconds later, an older man sat down in a chair next to us with a coffee. His white hair was slicked back and he was wearing a black button-down shirt, black jeans, and a belt with an enormous buckle. On his right hand was a garish gold ring and on his feet were the most amazing pair of cowboy boots I had ever seen. The brown leather rippled in shades of light caramel and gold and deep chocolate. My first thought was to sneer at his outfit. Where do you think you are, Texas? asked The Voice, and then I thought of the receptionist we just left and was flooded with a new shame.

I wanted to be nothing like that receptionist, nothing at all like her, so I looked at the man and said, “Those are some really nice boots.”

The man stretched out his legs and lifted the toe of one boot into the air. “Thanks,” he said. “They’re gator skin. I have four pairs.”

“Four pairs?” I asked, delighted, as I always am when someone has exactly what they want, when they unabashedly showcase more than I think any of us are allowed to have.

He nodded at me and I tried to imagine four pairs of those boots lined up in my bedroom closet. In my head I thought of the tiny wooden closet in our old Virginia house and once again, I remembered I was homeless.

“So how do you like our ice cream?” the man asked me and I nodded and then said, “Oh so this is your place?” because sometimes it takes me a while.

The man nodded again and I watched the sunlight flash on his tacky ring. “I own the Five Guys and the Popeye’s and I wanted to bring in something different,”he said.

I told the man that my friend owns a Five Guys at the ballpark in DC and the man said, “Charlie? I know Charlie. Are you from DC?”

I said that I was, that we just moved here. “Your husband on the base?” he asked and I told him that Scott was a Seabee, that he was part of the huge construction project on Camp Lejeune. “I met with some Seabees last week,” he said. “I’m trying to get Five Guys on the base.” He asked me more about Scott’s job and then we talked about DC for a while. Oliver asked if he could have the rest of my melting ice cream come and I gave it to him. “I lived in DC for fourteen years,” the man said, “I was the kicker for the Redskins. It’s a great city.”

“The Washington Redskins?” I asked, as if there were any other kind. I am not a football fan, but my father and brother are and I grew up around detailed conversations about Joe Namath and O.J. Simpson, Refrigerator Perry and Mean Joe Green. When I think of those long ago Saturday mornings, I can still hear the tinny theme song of ABC’s “Wide World of Sports.” I can hear Jim McKay’s voice as he announces … the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat.

I looked up at the sign in front of me: NFL MVP. “So that’s you?” I asked pointing to it. “You’re Mark Moseley?”

The man took a sip of his coffee and nodded. “And that’s a Super Bowl ring,” I said, looking at the thick gold band on his right hand and stating the obvious.

“Mmmhmm,” he said, holding it up. Someone came over then and Mr. Moseley regally rose from his chair and said, “I hope y’all come back and see us again.” And then to the man who joined him, he said, “She just moved from DC. She knows Charlie.” The boys held up their sticky fingers for me and I got up for some napkins and felt something else rise inside me. Maybe it was relief or maybe it was happiness and maybe it was the fact that I had felt seen by this man with the beautiful boots. Moving always has a way of making me feel invisible, as if by changing locations, I have erased some essential part of myself, some piece that the man with the Super Bowl ring just handed back to me.

I’m not who you think I am! I had wanted to scream at that receptionist, just as I had wanted to ask the NFL MVP, Who do you think you are? How little we think we are allowed. How much we think we need.

It was late in the afternoon so the boys and I left Sweet and headed back to our Hilton Home2 to find that once again, housekeeping hadn’t shown up. I set Oliver up with his first-grade workbook and gave Gus some crayons and construction paper. I unrolled my yoga mat in the space between the two beds. I knew I probably only had a few minutes, but I could do some sun salutations in that time. I could give myself back to myself.

Without my friends and the lush Virginia woods, without the comfort of the worn oak floors of my Virginia kitchen, without the hot Georgetown yoga studio, without the refrigerator full of kale and overflowing book shelves and a city to hate, who was I? I looked around the room at the things I had deemed essential: crayons, books, and Legos, a rice cooker and too many shoes, an expensive jar of red onion jam and a long flat sticky mat. How little I think I am allowed. How much I think I need to make up for this.

The discomfort of this discovery is fragile and sharp and I carry it the way you would a piece of broken glass or an armful of thorny roses, a burning match or a dying starfish, objects shaped like heartbreak, whose beauty and wreckage are inextricable. This move to Jacksonville has been a crucible I have stepped into, the heat and shimmer of concrete and sand a mirror to what lies inside of me: the elusive shadows of beauty and bright piles of wreckage.

I do a few sun salutations and then I walk over to Oliver. I put my hand on Gus’ neck and feel the lump there, the beautifully benign node. I remember the way my own heart beat a year ago when I took Gus to the pediatric cardiologist to check out his heart murmur. I remember the way I exhaled when the doctor told me that Gus had an innocent murmur, that I had nothing to worry about.

How lucky I am, I think, as I look around our tiny hotel room, how narrowly I have edged through those clear panes of disaster. I think of my penchant for drama and realize suddenly that moving is neither a disaster nor the end of the world. Disasters are the only disasters. The end of the world is the only end of the world. I stand still for a moment and listen to the boys tell me about their artwork. Gus’ healthy neck is bent over his paper and I see how little I need. I feel stuffed full of all all I have been allowed to have.

Uncomfortable

June 11, 2012 § 21 Comments

“No Meg, don’t hope it was a dream. I don’t understand it any more than you do, but one thing I’ve learned is that you don’t have to understand things for them to be.” – from A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle.

Jacksonville feels like a stain. It looks as dirty and tired as a bar after last call. We are staying in an extended stay hotel on Western Boulevard, the main business route, which is an aggregate of Old Navys and Olive Gardens, Walmarts and Wendy’s. The air smells like fried chicken and cigarette smoke and the sunlight bounces off all that asphalt. At night, shadowy packs of boys walk along the strip, their jeans low on their hips. Yesterday, I went to the grocery store and a man in a wife beater and flip flops leered at me. He parked his cart by the shelves of raw chicken thighs and made comments at women who walked by him. I turned sharply into the aisle with the detergent and held a box of Downey sheets up to my nose wondering how I ever could have complained about Washington, DC.

We will probably be staying at the Hilton Home2 until the beginning of August, when a house will be available for us on base. On the first floor of the hotel, a fitness center with a television is adjacent to a laundry room. Twice, I let the boys watch Disney Junior while I used the elliptical machine and slipped quarters into the washing machine. On Thursday, I struck up a conversation with another mother of two boys who is staying at the hotel because her house burned down last month. Marines in camouflage come out of other rooms on our floor, and from behind closed doors, I hear Southern accents and babies crying. I smell food being microwaved and Ramen noodles cooking. The night we arrived here, I had a quiet meltdown – conscious of the thin walls and my sleeping boys – thinking that at 39, I am too old to be living in a place that smells like someone else’s dinner. What was the point of the college degrees and all that striving? I thought back to another hotel room eight years ago in San Francisco. I was up all night helping the president of my company write her presentation and at five in the morning, I staggered off to Kinkos with it, thinking that finally, I was on my way. I would never in a million years have believed that I was on my way here to a town overflowing with soldiers.

Each place I have lived during the last six years has taught me something. In Philadelphia, Oliver was born, ironically, two hours from the town I drove 3000 miles away from when I was 21. In San Diego, I learned how to be an adult, a mother, and a wife. In Ventura, I was taught how to trust my heart and to believe in goodness. Washington DC taught me how to be alone and then how to be with people. I spent a year with this guy:

And despite being so lonely for my first year there, things like this began to happen:

Tonight I went for a walk along Western Boulevard, a four-lane highway with sidewalks but no crosswalks. After a while, my walk began to feel like a game of chicken with the pickup trucks and I started back to the hotel. I passed by Ruby Tuesday and the House of Pain tattoo parlor, Food Lion, and a dilapidated barber shop. Even though it was nine at night, a couple with a small child was going into Hooters. I wondered briefly if I should be afraid and then decided I shouldn’t. I figured I could outrun an attacker, and if I couldn’t, I would put up a good fight.

Coming towards me was a group of young Marines. Maybe I wasn’t as different from them as I thought. I too am the kind of person who would fight to the death to protect myself, and as they approached, I realized I am ashamed of this. The boys looked so innocent as they walked by me, so young. I wondered if they signed up to serve and protect and if they were surprised when they found out what was asked of them. Or maybe they weren’t. When I looked up, one of them said hello with a smile that lit up his face. And then they all looked at me for an instant, their faces lovely with youth.

I thought about how complicated it is to serve, how the word protect sometimes also means kill and how much that bothers me. I thought that some of those young boys might be headed off to a war I despise while others might build a school somewhere or save a child. They would all be trained to shoot and a few might have to pull the trigger when it counted. I thought about how much I hate being part of the military, how paying the cashier at the market sometimes feels like handing over blood money. And I thought of how proud I am that my gentle husband is a part of the same organization I hate, because he has watched over his own share of young men with such devotion. How contradictory it is to protect a freedom, how much freedom is taken away to accomplish that, how the choice to serve takes away so many other choices.

And then I thought about the first Power Yoga class I took at Downdog Yoga in Georgetown. For the last six months, that studio has served and protected me, which I never would have thought possible after that initial class, which I wasn’t sure I could even finish. On that morning, last July 4th, as we celebrated freedom, I was trapped in my own thoughts of how thirsty and tired and miserable I was. “I’m so hot,” my mind kept saying. ImsohotImsohotImsohot.

Gradually – and despite my best efforts not to – I fell in love with Power Yoga and began to practice at the Downdog studio four times a week, at least. On my second to last class there only six days ago, Kelly, who was teaching, told us that if we were uncomfortable, then we were in the right place. “That’s what you’ve come for,” she said. “To be uncomfortable and to see what’s underneath.”

As I finished my walk under the streetlights on a sidewalk that was still hot, I felt the same way I did in that first yoga class in Georgetown. I don’t want to know what’s underneath. I don’t want to see how I judge, how I hate, how I break every yogic value I strive for. I want to know why I am here in this strange town near the ocean. I want meaning and reason. I want validation that I am in the right place.

But the night gives me nothing other than the smell of fried chicken and hot concrete, the sound of my own sharp panic and stale discomfort. And maybe this is why I am here: to be uncomfortable. To crack off another layer. To cleanse myself here, in this city that looks toxic and not a single bit lovely in the dark.

War

April 22, 2012 § 26 Comments

When the soldier arrives,

bleeding in the doorway,

can you recognize him as yourself

and let him in?

– From Yoga Heart, Lines on the Six Perfections, by Leza Lowitz

There is something so strange about walking around inside someone else’s house and trying to decide if you want to live there or not. We do this every two years, each time we move, and I am always unsettled by the experience of being a voyeur as well as what people tend to tell you while you are peering behind their shower curtains.

We have never lived on a military base. As a single officer, Scott could always get a much nicer place off-base than on, and when he married me, I had absolutely no desire to live on a military installation. I am embarrassed to admit this, but after years of protesting wars, of voting for Gore and Kerry and Obama, being married to a soldier feels a bit like going to the dark side. The fact that my yoga classes and my children’s organic yogurts are paid for by the same money that funds the war in Afghanistan is a little too messy for me. So I avoid these feelings by living off-base, by pretending that I am not really a Navy Wife.

When we went to North Carolina last week, we assumed we would live in town, but what surprised me was that in Jacksonville, there doesn’t seem to be an “off-base.” Camp Lejeune only has housing for 25 percent of the soldiers who work there, so most people live outside the base in homes that were put together too quickly or in the apartment complexes that surround the gate.

Amy* opens the door of the first house for rent on our list.”Come on in,” she says in her delicate southern drawl. Her tanned feet are bare and she is wearing a bohemian tunic and a dark skirt. She looks like a shorter and younger Julia Roberts, her thick hair twisted on top of her head. Her home is immaculate and candles are burning in the dining room. There are flowers in the space above the fireplace where a TV would go, and Amy tells us that her children don’t watch television. She shows us the granite countertops and the hardwood floors and the walk-in closets, but all I can think of is the neighborhood, which looks vaguely apocalyptic. Coldwell Banker started building the subdivision in the middle of a field but then abandoned it partway through, perhaps because they ran out of money. All the pine trees have been cut down, but there are still flags marking lots that have not been sold and most of the homes have For Sale signs in front of them.

Amy then leads us up to the bonus room, which takes up half of the second story and she tells us about her 15-year-old son, Max, what a great kid he is and how the two of them were alone for years while her husband was deployed three times to Iraq and Afghanistan. Then, she tells us about her six-year old daughter whose birth took place while her husband was deployed. She explains that her labor came on so quickly that when her friend came to pick up Max, she told Amy to get into the car too so she could take her to the hospital. When they were halfway there, her friend had to call 911 and the paramedics delivered Amy’s baby in the back of their EMS truck in the Wal-Mart parking lot. “You know,” Amy says, “The big one on the road into Jacksonville?” She laughs and smiles. “I kept asking for something for the pain. Just a Tylenol or something but they kept telling me it was too late.”

Her daughter runs into the house then and asks for a bag. “What will you be wanting that for?” Amy asks, laughing again.

“For my pet butterfly.” Emma says.

Amy hands Emma a plastic sandwich bag and rolls her eyes at us. “You know what it’s like,” she says to me and I smile.

A second later, Emma is back. “Mommy, I need a spoon!”

Amy hands her the spoon and asks her why she needs it.

“The butterfly is dead,” Emma says and Amy’s mouth forms a silent, “Oh.”

The second house we look at is next door which is awkward, but I have already spoken to Penelope on the phone and she is expecting us. We are greeted by an enormous yellow lab and then Penelope comes to the door and says hello. The dog barks at me and I jump. “Oh, he’s all talk,” she says looking down at the dog, who now has his hackles raised.

In Penelope’s house, the place above the fireplace does have a TV and Cartoon Network is blaring even though no one is watching. Penelope’s husband is in the kitchen. He’s still in his combat boots and his camouflage pants. He is staring at us with his arms folded in front of his chest, and he takes the big dog from Penelope and holds him by the collar. Even though it’s cool in the house, I am sweating. Penelope is wearing a pair of blue scrubs with a stain on the front and a photo ID badge, which says she works in the lab. They chose linoleum and carpet for their home instead of hardwood and granite and someone has left a blue duffel bag on top of the stove.

Penelope tells me they have to move to San Diego and she looks as though she might cry. “I can’t find a place to rent there,” she says. “Every place I call has 100 people looking at it. Well, not really but you know what I mean.” I tell her about Carlsbad and Scripps Ranch and she nods. “We really want a place in Poway,” she says, “So I can sign my son up for football there. I hear the school is good.”

I nod and ask her if she’s been to San Diego before and she smiles. “Just once,” she says, “Right after Matt graduated. I drove out to Miramar to see him and then we drove back to Ohio together. I had just turned eighteen and all I cared about was being with him.” There is silence for a moment as a one-eyed tortoiseshell cat wanders into the room. Penelope tells me that she and her husband have been married for sixteen years now but it doesn’t feel that long. “We were going to retire in Jacksonville,” she says. “But then Matt called me from Afghanistan and said, ‘How do you feel about California?’ I thought he was joking. I said, ‘get out of here.'”

We tell them we’ll be in touch and we go outside to our car parked on the street. A man with a short, short haircut is driving an old Willys Jeep around the development. Because there are no trees, we can see him the entire way around and he waves to us.

Scott tells me that we can also live on base, that it might actually be nicer there and after he says that, it feels like someone is grabbing my stomach and squeezing it as hard as they can. We drove on base earlier that afternoon and it was nothing like the Navy bases we lived near in San Diego and Ventura. As we drove onto Camp Lejeune, a convoy of tanks was driving out. Marines with helmets and goggles were manning the guns and staring straight ahead. We had to stop at a cross walk while another group of soldiers ran across the street. One of them stepped out in front of our car, his feet wide apart and his hands clasped behind his back. He stared at us, expressionless until his group was safely on the other side.

That night, we meet one of Scott’s Marine friends for dinner. Jeff is a company captain in his early thirties and when Scott was stationed in Ventura, Jeff worked for him for a little while. In passing, Jeff mentions coming back from Afghanistan last August and I ask him what it’s like over there. “How do you go from fighting a war to this?” I ask, gesturing at the restaurant, which overlooks the water, and to the people who are eating fish tacos or sautéed grouper.

Jeff smiles as if I’ve said something funny. “The first time I came back from Iraq, I stayed drunk for 6 months.”

I ask him what happened after that, and he tells me that he heard Tony Robbins one day on a TED Talk and that changed him. “For my 30th birthday I went to Fiji to do Tony’s workshop.” He completed Tony’s workshops twice more, including once in Australia.

I tell Jeff that I have made Tony Robbins’ green soup before in my Vita Mix. Jeff nods. “Yeah, Healing Soup. During one workshop I did Tony’s cleanse for a week.”

“Did you walk on the hot coals?” I ask.

Jeff nods. “Three times,” he says. “I kept thinking cool moss. Cool moss.”

I ask him what he did the last time he was in Afghanistan and he tells me that he was in charge of about 250 men who were fighting there. I ask him if his soldiers are scared when they go out into battle and Jeff shakes his head. “They’ve been trained to kill for 7 months so it’s like we let them out of a cage. They want to fight. The trouble happens when they come back home. They don’t know how to not do that any more.” Jeff tells me that the perfect soldier is between 18 and 24 years old. “What was that Michael Moore movie called?” he asks and none of us remember. “Moore got some of it wrong. He filmed a kid in a tank in Iraq listening to “Fire Water Burn” as loud as it can go and shooting people like it was a bad thing. Well who else do you want defending you?”

Jeff tells us that sometimes, after they get back, he has to help soldiers stay out of trouble. “One guy,” he said, “It took 6 months before he stopped fighting in bars because they’re so used to that.” Jeff explains that the programs that try to help soldiers when they are home are more of a bureauocratic nightmare than a help. He tells us that he comes up with his own programs for helping his troops. “I try to find ways to set goals for them and motivate them. I try to help them move forward because they can’t go back.”

“What people don’t get,” he continues, “Is that when a Marine is in a company, for the first time in his life, he’s with a group of guys who won’t let him down. No matter what. Then he comes back from Afghanistan after a year and his girlfriend’s cheated on him and his buddies don’t show up and all he wants to do is go back to his company. But he can’t because the company doesn’t exist any more. It’s all different when he comes home.”

Later that night, back at the Swansboro Hampton Inn, where we are staying, I start to cry and I have trouble breathing. My heart starts to race and it feels like I have no skin so I climb into the bathtub, where things seem a little bit better. I stare up through the shower curtain at the stacked white towels and the extra rolls of toilet paper and then down at my left hand, where during graduation from my 200 hour yoga teacher training, another graduate wound a purple thread around my wrist and then tied it. We did this to symbolize something we wanted to bring into our lives, and when it was my turn, I said, “Faith.”

It occurs to me then that it is hypocritical of me to believe I am a spiritual person when everything is going my way, and then to shake my fist at the sky when things get scary. I wonder if maybe the reason I am sitting in a bathtub trying to breathe has less to do with living on a Marine base and more to do with the fact that I am now having to face the part of myself I have avoided since becoming a Navy Wife.

Before I had anything to do with the military, I went to an Ivy-League school and was cross-country captain. I met Scott when he was going to grad school at Stanford and for a while we lived in Palo Alto and spent too much money on Thai food on Saturday nights just because we could. For most of my life, I put all my faith in being special, which may just be another way of saying I think I am better than everyone else. Even my yoga teacher training was another exercise in being special, in becoming more spiritual. But it’s one thing to think we’re all one while chanting Om and wearing Lululemon and it’s another thing entirely to think I am one with the 18-year old soldier who is shooting the hajis and with the enemy who is shooting back, with the man in the combat boots and the dog who is all talk. Maybe I was sitting in a bathtub because I was having to face the part of me that doesn’t want to recognize the soldier as myself.

The next day I tell Scott I’m ready to check out some of the homes on base so we drive out to the end of Camp Lejeune by Bogue Sound. It’s mostly pine forest and salt water rivers. I think in North Carolina, they call it low country. “Wow,” Scott says, “This is nice.”

I have to agree. A bike path winds next to the road and the neighborhood has sidewalks. “This looks more off-base than off-base does,” I tell him.

We are visiting our friends Chris and Paige. Scott will be taking over Chris’s job as the officer in charge of construction on base and we drive through their neighborhood, which is quiet and faces the water. The homes are two-story Cape Cods with blue shutters and sunrooms on the side. When we arrive, Paige is outside under a tree, reading with her 7-year old son. After we say hello, she gives me a tour of their home with the refinished oak floors and the curving staircase that leads to the big bedrooms upstairs. She tells me that by living on-base, Scott won’t have to go through the traffic to get through the gate, which sometimes can take over an hour. “But it’s stressful here too,” she continues. “The Marines come back from Afghanistan and their lifestyle is a little bit different if you know what I mean.” As if on cue, a police car drives into her neighbor’s driveway and Paige sighs.

We go back downstairs and I follow Paige to the kitchen where she makes a smoothie for her son, Sam, and then leads me outside to the backyard. “Sam’s tutor’s husband was on the Osprey that went down in Morocco,” she says quietly so no one will hear. “You see a lot here. You see guys with service dogs because of their PTSD and then you see the men walking around without an arm or a leg and it hits you.”

I tell Paige a bit about what I have seen over the past couple of days and how sheltered I have been from the fighting and the training and the deployments over the past decade. I think of how I tried to pretend that I wasn’t a Navy Wife as if it were possible to repudiate a war. I told myself that I wasn’t responsible for the war because I never voted for it, but really I am culpable if only because I live in the United States, because I expect there to not be a sniper at the end of my street, and because when I flip the switch, I expect the light to turn on. I am responsible for the war because these expectations necessitate a military that is ruthless and unflinching. They necessitate a service that trains 18 to 24 year olds how to fight so that I don’t have to carry a gun.

In the neighbor’s driveway, the police car is still there. We stare at it for a moment and then Paige shakes her head. “The war is right here,” she says. “It’s right here.”

*Some names have been changed

Pratyahara

April 6, 2012 § 14 Comments

“Yoga is the practice of tolerating the consequences of being yourself.” – Bhagavad Gita

“Where can you run to escape from yourself?

Where you gonna go?

Where you gonna go?

Salvation is here.” – Switchfoot

A few weeks ago, on a cold, rainy, Saturday, I was cleaning the bathrooms and washing our wood floors. Much has been written lately about the virtues of cleaning, but I am not convinced that these aren’t written by people with maids. By the time I was halfway through I was cranky, and I stopped in front of the upstairs window that looks out into our steep backyard to see if it was still raining. I watched the drizzle for a minute and was about to pick up the paper towels again but noticed two bright blue jays perched on a bare branch below. It’s not that blue jays are rare, exactly, but still, I don’t see them very often, especially not two, their wings too bright for this day, their bodies too fat for the thin branch they were bobbing on. As I stood, I saw a third jay perched high up in the sapling, and then, while I was still marveling at my luck, another one landed, its square wings folding under him. Despite the day and the chore and the remaining bathroom, I felt delight flutter in my throat. It felt like more than I was allowed to have.